interviews

Elena Ruiz Sastre: "We cannot continue to approach art only from historiographical concepts, it is an absolutely intellectual message"

Elena Ruiz Sastre, born in Soria in 1960, is a renowned art historian and cultural manager who has been the director of the Ibiza Museum of Contemporary Art (MACE), one of the first contemporary art museums in Spain, since 1990. With a solid background in Art History and previous teaching experience, she has stood out for her work in expanding and consolidating the museum's collection, as well as for her ability to position MACE as a reference center in the artistic scene.

Under her direction, the museum has grown in prestige and influence, especially thanks to her work in linking Ibiza with avant-garde movements such as the Ibiza 59 Group, which attracted prominent abstract artists. In addition, Elena has promoted innovative projects that integrate art with society, leading educational and therapeutic programs aimed at bringing art closer to different social groups, placing special emphasis on the emotional and social impact of contemporary art.

Ricard Planas Camps. To begin with, how do you see the return of craftsmanship in the world of contemporary art?

Elena Ruiz Sastre. Look, I just came back from the Venice Biennale, where there is a great presence of contemporary textiles and crafts, and it seems that there will be more and more of them. There is a particularly strong Latin American imprint in the discourse of artists linked to the indigenous world, who recover traditional techniques of textiles, ceramics and decoration. All of this takes us back to a primitive world where these practices had a practical function, but contemporary art is moving away from this practical utility. A clear example is the work of Albert Pinya, a young Mallorcan artist who has exhibited in Ibiza and who has worked with ceramics. He has created forms inspired by Phoenician eggs, which were used to store the ashes of the deceased. Artists often connect with the primitive, with the ancestral, and with what is deeply human and cultural.

RPC. And how do you see the relationship with the digital sphere?

ERS. Digital does not replace face-to-face, but rather complements it. I believe that we are faced with the development of very powerful technological tools. The challenge is to educate ourselves to make good use of these tools and we must know how to dose them, without allowing them to replace us or anesthetize us to the point of becoming robots that we only know how to consume.

RPC. Psychologically, there are already some alarming studies on the subject. Especially in terms of addictions in young children.

ERS. Yes, it has an anesthetic component. From the point of view of neurology, the emotions that are recorded in our brain, especially in the amygdala, are linked to experiences. What is fixed is an emotion that is part of a lived experience. When these experiences are painful, the human mind tends to deceive itself and, often, anesthetizes the memories that cause us pain. However, if we understand the purpose of pain, we will not need anesthetics, because pain helps us to know ourselves better, it is part of us.

RPC: How do you perceive the relationship between art and pain?

ERS. Art is a path that, from my point of view, does not always lead to happiness. Artists often address painful topics, but despite this, art is a path to knowledge. The most direct is music. Suddenly it sounds and already transports us to emotions, to worlds, to imaginations... Words, poetry, on the other hand, lead us to reflection.

RPC: They teach us to read and write, but on the other hand, in terms of visual arts education is scarcer. The museum has a significant flow of schools and children, can you tell us a little about this line of the museum?

ERS. Education, especially that promoted by the competent bodies, seems well-intentioned to me, but I think it lacks adequate attention to the emotional sphere. If you study the history of art, you can obtain many keys to understanding artists like Rubens or Velázquez, since this involves investigating the historical context, politics and social relations of that time. This helps you understand why these artists painted in that way, but art history will not give you the deep meaning of their works; for that, other tools of knowledge are needed.

RPC: Which ones?

ERS. These tools often come from research, especially on emotions, and emotional education comes into play, which I consider fundamental. At the museum, for example, we have a program called "Therapeutic Museum" and we organize visits in this direction. When people arrive at the museum, they do not enter directly into the exhibition rooms; first they go through an educational room where they do breathing exercises. This allows them to disconnect from what they brought from the street and enter another space. It is important to facilitate this transition because many visitors are not familiar with the museum environment. Maybe I know more about art history because I have studied it, but emotionally, we are all similar. Emotions such as disgust, fear, sadness or joy are universal, and here there is no possible segregation, nor barriers of language, gender or knowledge.

RPC. A few weeks ago I interviewed Beatriz Herráez from Artium and she emphasized the historical debt that exists in her collections regarding the visibility of women. What do you think about that?

ERS. Sometimes you can create inclusive narratives on gender issues, but it's not always easy. For example, at the Museum, our starting point was the Ibiza 59 Group, where there was only one woman. With the director of Es Baluard at the time, Imma Prieto, we proposed that they, with more financial capacity, make an exhibition dedicated to Katja Meirowsky, the only female member of the group, and manage to visualize her more and better. There is another interesting case. Two other museums depend on the MACE: the Puget and the Casa Broner, which we manage as satellite spaces, allowing us to exhibit both traditional figurative painting from the islands and the avant-garde. The Casa Broner was donated by Gisela StraussBroner, the widow of the architect and painter Broner. When we received the Broner legacy, the plans went to the College of Architects, while we received the house and some paintings. Years later, researching them, I discovered with surprise that they were signed by her. Although Gisela StraussBroner may not have been a painter by profession, she had played a submissive role, perhaps voluntarily, in a family structure where her husband shone. These four works have already been integrated into two temporary exhibitions and we intend to incorporate them into the Broner House permanently. This little story is enough to empower the figure of Gisela StraussBroner and place her on an equal footing.

RPC. Let's talk about collections. How is the museum's collection made up?

ERS. It arises from the nucleus of Ibiza 59, the avant-garde group of the islands. In the museum, we have a presence that includes personalities such as the thinker Walter Benjamin and his relationship with the photographer Raoul Hausmann, who was on the island in the 1930s. But most of the artists we highlight are from after the 1950s, such as Isabel Echarri and Giorgio Pagliari. There are also other artists who, despite not being part of the Ibiza 59 Group, left their mark on the island, such as Emil Schumacher, Hans Kaiser, Will Faber and Joan Semmel. In the 1950s, many Germans arrived in Ibiza to settle, seeking to recreate this bucolic image of paradise.

RPC. Now that he's talking about paradise... The historian Lluís Costa, together with Bruno Ferrer, have just published 'The Destruction of Paradise', the letters of Walter Benjamin, who was already beginning to anticipate the conflict with tourism.

ERS. Walter Benjamin is a luminous voice and precursor of many ideas, but he still maintains an essence of late Romanticism. In fact, the Romantic tradition extends well into the 20th century. An interesting example is the case of Ivan Spence, the first great gallery owner in Ibiza. I have his unpublished memoirs, in which he tells an anecdote from the 1960s: he bought a cart and a donkey to move around the island, and one day, arriving at Café Montesol, he tied the donkey to a tree. When a policeman forbade him to park there, Spence exclaimed: "I'm leaving Ibiza, it's not what it used to be." This sentence reflects how, for him, the 1960s already seemed like the end of an era. Interestingly, today, from the perspective of 2024, we see the 60s as an idyllic time, but for those who lived at that time, it already seemed that the essence of Ibiza was being lost.

RPC. Let's delve deeper into the binomial tourism and culture.

ERS. Tourism is generating a great imbalance, which is obvious. The tourist boom of the 1960s transformed this island, previously economically poor, into a place with enormous development. Now it is obvious that it needs to be regulated, since there are many shortcomings that need to be studied carefully. It is necessary to moderate mass tourism, as well as the high inflation caused by tourism by people with great purchasing power who buy properties and raise the prices of all types of businesses. From our point of view, speaking from the museum, we have not experienced any type of crisis.

RPC. Has it helped in any way?

ERS. I want to believe that it collaborates positively. We are not experiencing an overflow of visitors. We are optimistic because what we offer is being "consumed" in moderation.

RPC. Visitable warehouses are a very interesting trend, but warehouses have limits, you can't grow infinitely.

ERS. The project of the visitable warehouse is a wish that we were able to fulfill last year with an exhibition. This museum has a lot of history. It was conceptually born in 1964 with the Ibiza Biennial, and the opening materialized between 1969 and 1972. It is one of the first contemporary art museums in the Spanish State, outside of Madrid and Barcelona, which at that time did not have a fixed headquarters, despite being recognized. It was created during the late Franco regime with a clear purpose of political propaganda, but over time it became a temporary museum, only open during the summer season. It later became a permanent museum, although this stage did not last long.

RPC. You have managed to consolidate this initiative.

ERS. I have been at the head of this museum for longer than any other director, which brings stability, as well as good dynamics and some perhaps not so good ones (smiles). Thanks to this, we have been able to keep the museum open stably throughout the year, and this has allowed us to inventory the collections, realizing their heterogeneity. One of my missions is to re-investigate the old Biennale funds to recover this legacy.

RPC. Do you have any line of study or scholarship in this regard?

ERS. We do not have research grants. We do the research ourselves directly from the museum. For example, I currently have a project in mind: to bring to European museums what happened in Ibiza, to explain to Europeans what the German artists did here and to transmit this message of culture and civilization. They knew how to transform the drama. The great story that this museum tells, especially in the chapter of the Ibiza 59 Group, is that they were able to turn the drama into a work of art and into life.

RPC. When is your memoir due?

ERS. I don't know! (smiles). I've written and published a lot, but people have the hours they have. I don't want to apologize, but I think I have other priorities. I was a divorced woman, who had to raise three children, and run a museum, while we created the Broner House and the Puget Museum, which didn't exist before. Maybe it will be something I consider later.

RPC. This is a very important legacy. How do you see the future in ten years?

ERS. I see that all this is an enormous capital that will only grow. There is no other possibility; it cannot decrease. Everything that is created constructively is something that must be maintained and improved, and I have no doubt about it.

RPC. Public policies aimed at culture tend to consolidate but usually do not grow. Do you think the private sector should be more involved?

ERS. The administrations have a limit. Currently, I have a president of the board of trustees with enormous enthusiasm for culture. Last year, the museum's budget increased, and I see great support from the Balearic Government, which provides us with annual nominative subsidies. Speaking to Pedro Vidal, who is the Secretary of Culture, I also notice his enthusiasm. In terms of private action, there is an association of friends of the museum that is agile and passionate, and always provides support through donations, such as those from Rosselló and José Luis Blanquer, which we have deposited here at the museum.

RPC. There is also the issue of the climate emergency and how culture responds to zero kilometer, to sustainable practices, to the use of renewable energies in its facilities...

ERS. Apart from learning from past mistakes, we now find ourselves with a new paradigm that we have to solve. And how do we do it? It's not easy. For example, in the museum there is an air conditioner... During the pandemic, it was said that if we removed the air conditioners from public places that had been closed, the air would be cleaner. In museums they cannot do without them to preserve the works of art, but if we can have renewable energies to minimize the impact. It's a matter of balance. During the pandemic, I came as authorized personnel with a security guard every day to the museum; it was spooky to walk down the street when no one was there. We had to regulate the temperature and humidity to ensure that the works were not damaged.

RPC. How did you approach the whole Covid issue? What positive and negative things do you think it has left behind?

ERS. We approached the situation with a lot of reflection. The positive consequences were this didactic approach. We cannot continue to approach art only from historiographical concepts, it is an absolutely intellectual message. We are asking people to understand what conceptual art or abstract informalism is, when people come who have no prior knowledge. We have to present art through emotions, and the pandemic taught us this. The pandemic gave us a great lesson in humanity and we placed ourselves at the level of people, leaving the intellectual discourse to specialists.

RPC. What came out of it?

ERS. We created a much friendlier museum and abandoned discourses that could seem cryptic, allowing people to access discourses that were more approximate from an emotional point of view. However, after covid the world has worsened in the repetition of the same mistakes and in the hypocrisy regarding climate change.

RPC. Have you given any presentations on these environmental issues?

ERS. Santi Moix's exhibition is a reflection on flora and nature, and Joana Vasconcelos's last year was also. We don't do politics or make political headlines; we simply work on it.

RPC. Xavier Barral has always said that every human act is political.

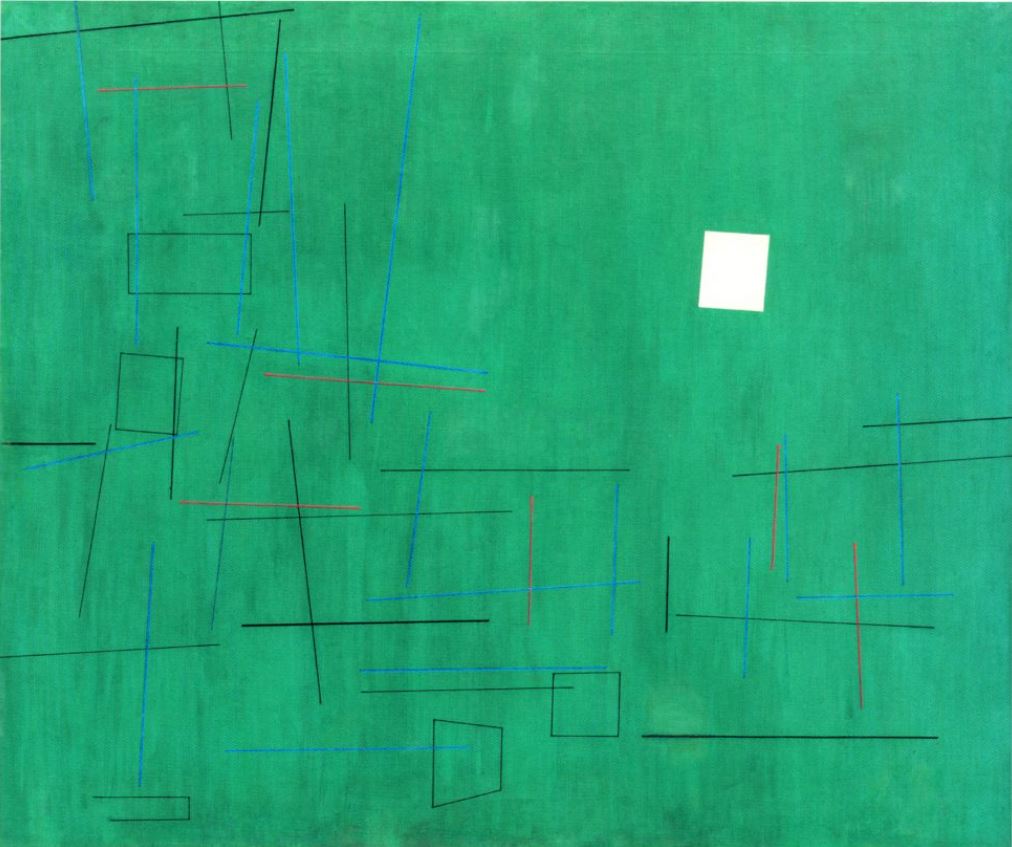

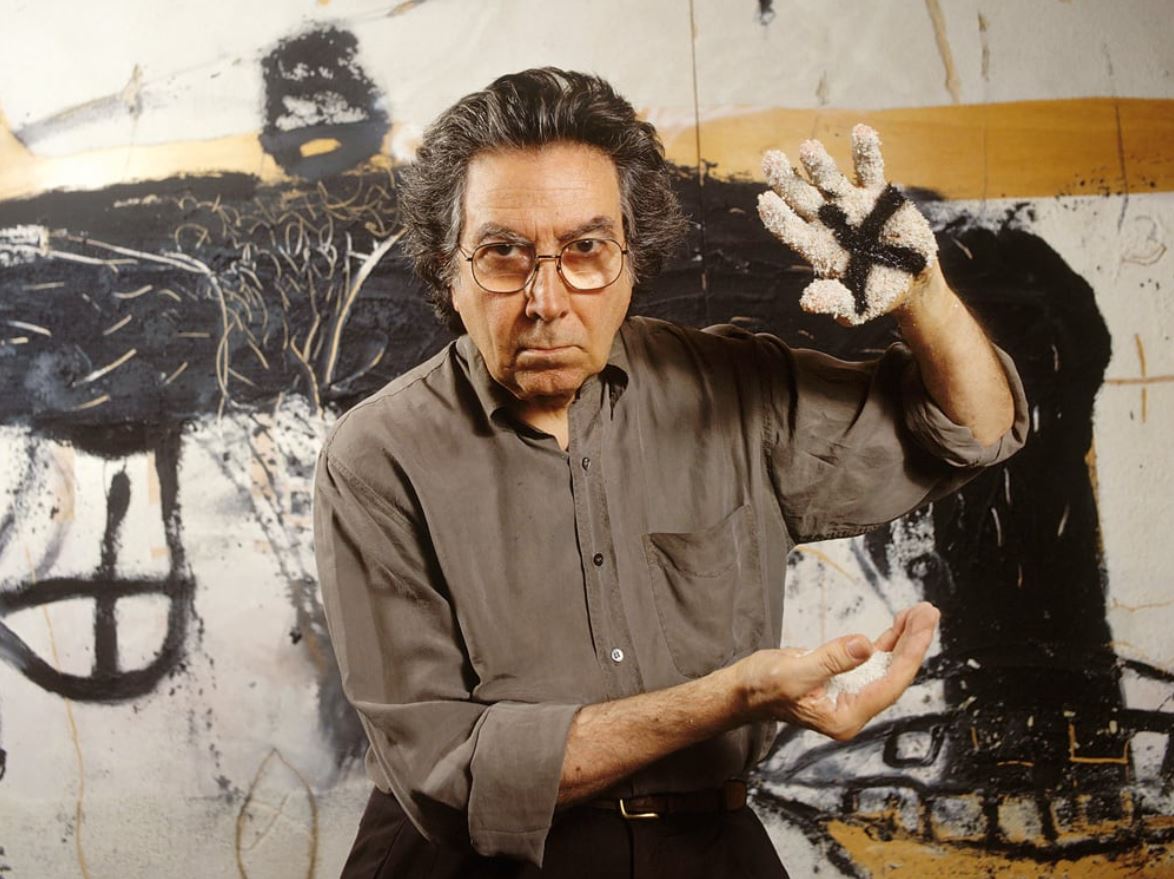

ERS. The consequence may be political, from my point of view, but we convey the artist's message. Joana Vasconcelos lent us a piece, 'Valkyrie Crown', which is wonderful and revolves around recycling. Joana works by employing Lisbon women with ancestral fabrics, recovering pieces that are not thrown away. Therefore, we have a work made by women with recycled materials, which includes their work and a piece of ribbon. This is a great lesson in ecology. As for the work by Santi Moix, I titled it 'La Scoperta del Fuoco', in reference to a painting by Tintoretto that is in Venice.

RPC. I see that you are passionate about history, myths and their interpretation...

ERS. Yes, one of my interests is teaching and communication, and the other is myths and the interpretation of symbols in the contemporary. I believe that artists sometimes consciously and sometimes unconsciously use a language of ancestral symbols that, although they seem hermetic, are loaded with meaning. Santi Moix's work presents a paradisiacal universe. On the one hand, it is an Eden, and on the other, the flower is the most concrete symbol of the ephemeral condition of life, which we can observe with our own eyes when spring arrives and the flowers bloom, only to disappear after a few months. Santi traveled the entire island of Menorca, where he made charcoal drawings, and then walked around Ibiza, collecting small species of orchids that grow spontaneously on the island and other local flowers.

RPC. It's our Sánchez Cotán in the 21st century version

ERS. I do not mention Sánchez Cotán in the text, but I do talk about two female artists who painted unknown flowers: Barbara Dietzsch and Maria van Oosterwijck. There are some surprising coincidences that left Santi speechless, because he sent him photos of a painting of a thistle made by Barbara Dietzsch, which is from the 18th century, and a drawing of a thistle made by him, and they turned out to be practically identical. Santi's exhibition also symbolizes the birth of nature. In the text, I also mention a painting by Lucas Cranach, whom I consider one of the wisest painters in history. His painting of Eden manages to represent all the episodes in the same plane, since he had no other way to do it. On the other hand, Santi does the same but in reverse: we, the visitors to the exhibition, are the first human beings to inhabit Eden, while around us we observe the birth of nature.

RPC. Interesting reflection to end with.

ERS. According to the Pentateuch, in Genesis, God commands the Earth to flourish. Furthermore, the Enuma Elish, a pre-Biblical poem attributed to Ephren (later sanctified as Saint Ephren by Christians), expresses a similar idea: a god commands the Earth to flourish and germinate. This initial command is similar to the idea of Heraclitus, who speaks of fire as the origin of life. We can also recall the myth of Prometheus, who uses fire as a symbol of life. Prometheus is the hero who steals fire and gives it to humans, suffering punishment from the gods for his action.

'La Scoperta del Fuoco', Santi Moix

'La Scoperta del Fuoco', Santi Moix