interviews

Elena Ruiz Sastre: "We can't continue to approach art only from historiographical concepts, we have to present it through emotions!"

Elena Ruiz Sastre, born in Soria in 1960, is a renowned art historian and cultural manager who, since 1990, has been the director of the Museu d'Art Contemporani d'Eivissa (MACE), one of the first contemporary art museums in 'Spain. With a solid background in Art History and previous teaching experience, he has stood out for his work in expanding and consolidating the museum's collection, as well as for his ability to position the MACE as a center of reference in the artistic scene.

Under his direction, the museum has grown in prestige and influence, especially thanks to his work to link Ibiza with avant-garde movements such as the Ibiza 59 Group, which attracted prominent artists of abstract art. In addition, Elena has promoted innovative projects that integrate art with society, leading educational and therapeutic programs aimed at bringing art closer to different social groups, placing special emphasis on the emotional and social impact of art contemporary

Ricard Planas Camps. To begin with, what does the inclusion of an exhibition like Santi Moix's in the Contemporary Art Museum of Ibiza entail? How do you see the relationship with the current craft that is returning to contemporary art?

Elena Ruiz Tailor. Look, I've just come back from the Venice Biennale, where there's a huge presence of contemporary fabrics and crafts, and it looks like there's going to be more and more. A strong Latin American imprint is particularly noticeable in the discourse of artists linked to the indigenous world, who recover traditional techniques of fabrics, ceramics and decoration. All of this takes us back to a primitive world where these practices had a practical function, but contemporary art moves away from this practical utility. A clear example is the work of Albert Pinya, a young Mallorcan artist who has exhibited in Ibiza and who has worked with ceramics. He has created shapes inspired by Phoenician eggs, which were used to store the ashes of the dead. Artists often connect with the primitive, with the ancestral, and with that which is deeply human and cultural.

PRC And how do you see the relationship with the digital field?

ERS. The digital does not replace the face-to-face, but complements it. I think we are facing the development of very powerful technological tools. The challenge is to educate ourselves to make good use of these tools and we must know how to dose them, without allowing them to replace us or anesthetize us to the point of becoming robots that only know how to consume.

PRC Psychologically, there are starting to be somewhat alarming studies on the subject. Especially at the level of addictions in young children.

ERS. Yes, it has an anesthetic component. From the point of view of neurology, the emotions that are recorded in our brain, especially in the amygdala, are linked to experiences. What remains fixed is an emotion that is part of a lived experience. When these experiences are painful, the human mind tends to deceive itself and often anesthetizes the memories that cause us pain. However, if we understand the purpose of pain, we will not need anesthetics, because pain serves us to know ourselves better, it is part of us.

RPC: How does this perceive the relationship between art and pain?

ERS. Art is a path that, from my point of view, does not always lead to happiness. Artists often deal with painful subjects, but despite this, art is a path to knowledge. The most direct is the music. Suddenly it sounds and already transports us to emotions, to worlds, to imaginations... Words, poetry, on the other hand, lead us towards reflection.

RPC: They teach us to read and write, but on the other hand, at the visual arts level, education is scarcer. In the museum they have an important flow of schools and nurseries, can you tell us a little about this line of the museum?

ERS. Education, especially that promoted by the competent bodies, seems well-intentioned to me, but I think it lacks adequate attention to the emotional sphere. If you study art history, you can get many keys to understanding artists like Rubens or Velázquez, as this involves researching the historical context, politics and social relations of that time. This helps you understand why these artists painted the way they did, but art history won't give you the deep meaning of their works; for this other tools of knowledge are needed.

RPC: Which ones?

ERS. These tools often come from research, especially about emotions and emotional education comes into play, which I consider fundamental. At the museum, for example, we have a program called "Therapeutic Museum" and we organize visits in this direction. When people arrive at the museum, they don't go straight into the exhibition halls; first they go through a teaching room where they do breathing exercises. This allows them to disconnect from what they bring from the street and enter another space. It is important to facilitate this transition because many visitors are unfamiliar with the museum environment. Maybe I know more about art history because I've studied it, but emotionally, we're all the same. Emotions such as disgust, fear, sadness or joy are universal, and here there is no possible segregation, no barriers of language, gender or knowledge.

PRC A few weeks ago I interviewed Beatriz Herráez of Artium and she emphasized the historical debt that her collections owe to the visibility of women. What do you think?

ERS. Inclusive narratives can sometimes be created on gender issues, but it is not always easy. For example, at the Museum, our starting point was the Ibiza 59 Group, where there was only one woman. With the director of Es Baluard at the time, Imma Prieto, we proposed that they, with more financial capacity, hold an exhibition dedicated to Katja Meirowsky, the only female member of the group, and manage to visualize her more and better. There is another interesting case. Two other museums depend on MACE: the Puget and Casa Broner, which we manage as satellite spaces, allowing us to exhibit both the traditional figurative painting of the islands and the avant-garde. The Broner House was donated by Gisela StraussBroner, the widow of the architect and painter Broner. When we received the Broner bequest, the plans went to the College of Architects, while we received the house and some paintings. Years later, researching them, I discovered to my surprise that they were signed by her. Although Gisela StraussBroner may not have been a painter by trade, she had played a subdued role, perhaps willingly, in a family structure where her husband shone. These four works have already been integrated into two temporary exhibitions and we intend to incorporate them into Casa Broner permanently. This little story is enough to empower the figure of Gisela StraussBroner and place her on a plane of equality.

PRC Let's talk about collections. How is the museum made up?

ERS. It arises from the nucleus of Ibiza 59, the avant-garde group of the islands. At the museum, we have a presence that includes personalities such as the thinker Walter Benjamin and his relationship with the photographer Raoul Hausmann, who was on the island in the 1930s. But most of the artists we highlight are from after the 1950s, such as Isabel Echarri and Giorgio Pagliari. There are also other artists who, despite not being part of the Ibiza 59 Group, left their mark on the island, such as Emil Schumacher, Hans Kaiser, Will Faber and Joan Semmel. In the 1950s, many Germans arrived in Ibiza to settle, seeking to recreate this bucolic image of paradise.

PRC Speaking of paradise... The historian Lluís Costa, together with Bruno Ferrer, have just published 'The Destruction of Paradise', the letters of Walter Benjamin, who was already beginning to anticipate the conflict with tourism.

ERS. Walter Benjamin is a luminous voice and precursor of many ideas, but still maintains an essence of late-romanticism. In fact, the romantic tradition extends well into the 20th century. An interesting example is the case of Ivan Spence, the first great gallerist in Ibiza. I have his unpublished memoirs, in which he tells an anecdote from the 60s: he bought a cart and a donkey to move around the island, and one day, arriving at Café Montesol, he tied the donkey to a tree. When a policeman forbade him to park it there, Spence exclaimed: "I'm leaving Ibiza, it's not what it used to be." This sentence reflects how, for him, the 60s already seemed like the end of an era. Interestingly, today, from the perspective of 2024, we see the 60s as an idyllic time, but for those who lived at that time, it already seemed that the essence of Ibiza was being lost.

PRC Let's delve into the combination of tourism and culture.

ERS. Tourism is generating a great imbalance, which is obvious. The tourism boom of the 1960s transformed this previously economically poor island into a place of enormous development. Now it is clear that it needs to be regulated, as there are many shortcomings that need to be well studied. It is necessary to moderate mass tourism, as well as the high inflation caused by the tourism of people with great purchasing power who buy properties and raise the prices of all kinds of businesses. From our point of view, speaking from the museum, we have not experienced any kind of crisis.

PRC Did it help in any way?

ERS. I want to believe that it collaborates positively. We do not experience an overflow of visitors. We are optimistic that what we offer is being "consumed" in moderation.

PRC Visitable warehouses are a very interesting trend, but warehouses have limits, you can't grow infinitely.

ERS. The visitable warehouse project is a wish that we were able to fulfill last year with an exhibition. This museum has a lot of history. It was conceptually born in 1964 with the Ibiza Biennale, and the opening materialized between 1969 and 1972. It is one of the first contemporary art museums in Spain, outside of Madrid and Barcelona, which at that time did not they had a fixed seat, despite being recognized. It was created during the late Franco regime with the clear purpose of political propaganda, but over time it became a temporary museum, only open during the summer season. It then became a permanent museum, although this stage was short-lived.

PRC You have managed to consolidate this initiative.

ERS. I have been at the helm of this museum longer than any other director, which brings stability as well as some good dynamics and some maybe not so good dynamics (smiles). Thanks to this, we have been able to keep the museum open stably throughout the year, and this has allowed us to inventory the collections, realizing their heterogeneity. One of my missions is to re-investigate the Biennale's old holdings to recover this legacy.

PRC Do you have any line of study or scholarship in this regard?

ERS. We do not have research grants. We do the research directly from the museum. For example, I currently have a project in mind: to bring to European museums what happened in Ibiza, to tell Europeans what German artists did here, and to convey this message of culture and civilization. They knew how to transform the drama. The great story that this museum tells, especially in the chapter of the Ibiza 59 Group, is that they were able to turn drama into a work of art and into life.

PRC For when your memoir?

ERS. I don't know! (smiles). I have written and published a lot, but people have the hours we have. I don't want to make excuses, but I think I have other priorities. I have been a divorced woman, who has had to raise three children and run a museum, while we were creating the Broner House and the Puget Museum, which did not exist before. Maybe it will be something I think about later.

PRC This is a very important legacy. How do you see the future in ten years?

ERS. I see all this as a huge capital that will only grow. There is no other possibility; cannot decrease. Everything that is constructively created is something that needs to be maintained and improved upon, and I have no doubt about that.

PRC Public policies aimed at culture tend to consolidate but usually do not grow. Do you think the private sector should get more involved?

ERS. Administrations have a limit. Currently, I have a board president with an enormous enthusiasm for culture. Last year, the museum's budget increased, and I see great support from the Balearic Government, which provides us with annual nominative subsidies. Talking to Pedro Vidal, who is Secretary of Culture, I also notice his enthusiasm. As for private action, there is an association of friends of the museum that is agile and passionate, and always provides support through donations, such as those of Rosselló and José Luis Blanquer, which we have deposited here at the museum.

PRC There is also the issue of the climate emergency and how culture responds to kilometer zero, to sustainable practices, to the use of renewable energy in its equipment...

ERS. Apart from learning from past mistakes, we now find ourselves with a new paradigm that we must resolve. And how do we do it? It's not easy. For example, in the museum there is an air conditioner... During the pandemic, it was said that if we removed the air conditioners from public places that had been closed, the air would be purer. In museums they cannot do without it to preserve works of art, but if we can have renewable energy to minimize the impact. It's a matter of balance. During the pandemic, I came as authorized staff with a security guard to the museum every day; it was spooky walking down the street when no one was there. We had to regulate the temperature and humidity to ensure that the works were not damaged.

PRC How did you approach the whole Covid thing? What positive and negative things do you think he left behind?

ERS. We approached the situation with a lot of thought. The positive consequences were this didactic approach. We cannot continue to approach art only from historiographical concepts, since it is an absolutely intellectual message. We're asking people to understand what conceptual art or abstract informalism is, when they come from people who have no prior knowledge. We have to present art through emotions, and the pandemic taught us that. The pandemic gave us a great lesson in humanity and we stood at the level of the people, leaving the intellectual discourse for the specialists.

PRC What came of it?

ERS. We created a much friendlier museum and abandoned discourses that could seem cryptic, allowing people to access discourses that are more emotionally approachable. Now, after covid the world has gotten worse in repeating the same mistakes and hypocrisy regarding climate change.

PRC Have you given any exposure on these environmental issues?

ERS. Santi Moix's exhibition is a reflection on flora and nature, and Joana Vasconcelos's last year was also one. We don't do politics or launch political headlines; we just work on it.

PRC Xavier Barral has always said that everything human is political.

ERS. The consequence can be political, from my point of view, but we convey the artist's message. Joana Vasconcelos lent us a piece, 'Valkyrie Crown', which is wonderful and revolves around recycling. Joana works by giving jobs to Lisbon women with ancestral fabrics, recovering pieces that are not thrown away. Therefore, we bring a work made by women with recycled materials, which includes their work and a piece of tape. This is a great lesson in ecology. As for Santi Moix's work, I titled it 'La Scoperta del Fuoco', referring to a painting by Tintoretto that is in Venice.

PRC I can see that he is passionate about history, myths and their interpretation...

ERS. Yes, one of my interests is teaching and communication, and the other is myths and the interpretation of symbols in the contemporary. I believe that artists use sometimes consciously and sometimes unconsciously a language of ancestral symbols that, even if they seem hermetic, are loaded with meaning. Santi Moix's work presents a paradisiacal universe. On the one hand, it is an Eden, and on the other, the flower is the most concrete symbol of the ephemeral condition of life, which we can observe with our own eyes when spring comes and the flowers bloom, to disappear in the after a few months Santi toured the entire island of Menorca, where he made charcoal drawings, and then walked around Ibiza, collecting small species of orchids that grow spontaneously on the island and other local flowers.

PRC It is our Sánchez Cotán in the 21st century version

ERS. I do not mention Sánchez Cotán in the text, but I do talk about two female artists who painted unknown flowers: Barbara Dietzsch and Maria van Oosterwijck. There are some amazing coincidences that blew Santi's mind, because he sent her photos of a painting of a thistle by Barbara Dietzsch, which is from the 18th century, and a drawing of a thistle by him, and they were practically identical. Santi's exhibition also symbolizes the birth of nature. In the text, I also name a painting by Lucas Cranach, whom I consider one of the wisest painters in history. His picture of Eden manages to represent all the episodes in one plane, since he had no other way to do it. On the other hand, Santi does the same but in reverse: we, the visitors to the exhibition, are the first human beings to inhabit Eden, while around us we observe the birth of nature.

PRC Interesting reflection to finish.

ERS. According to the Pentateuch, in Genesis, God commands the Earth to blossom. Also, the Enuma Elish, a pre-biblical poem attributed to Ephren (later canonized as St. Ephren by Christians), expresses a similar idea: a god commands the Earth to blossom and germinate. This starting order is similar to the idea of Heraclitus, who speaks of fire as the origin of life. We can also remember the myth of Prometheus, which uses fire as a symbol of life. Prometheus is the hero who steals fire and gives it to humans, suffering the punishment of the gods for his action.

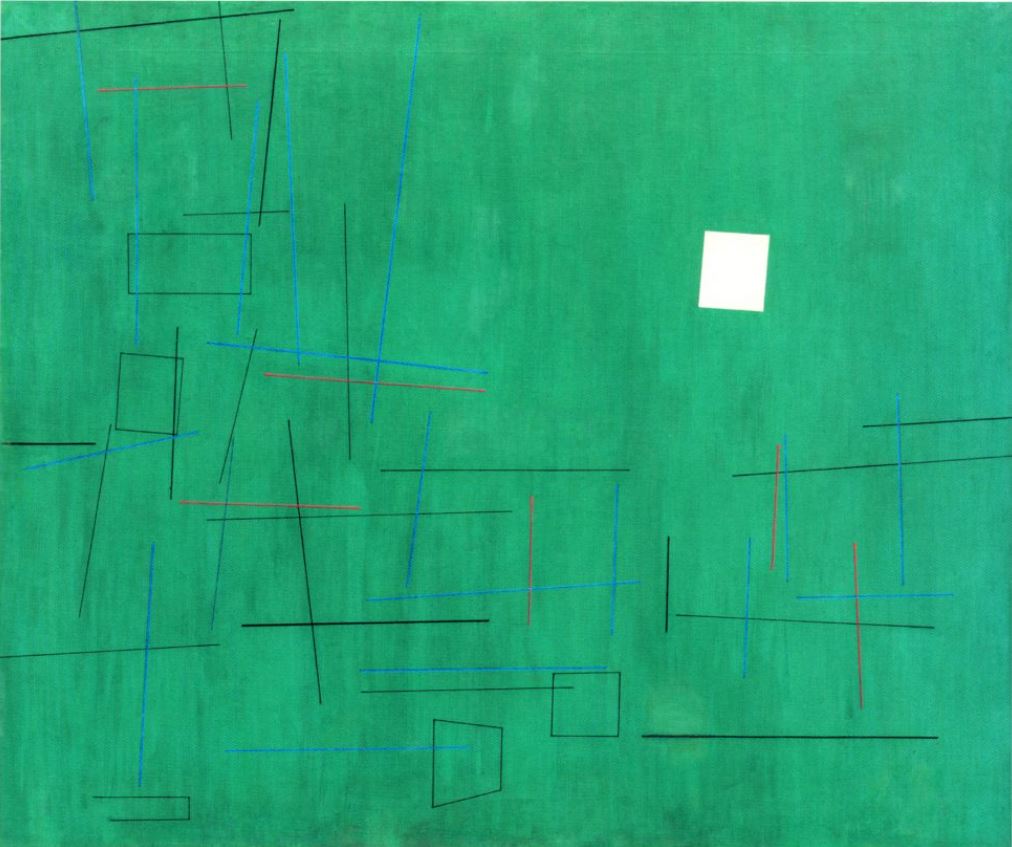

'La Scoperta del Fuoco', Santi Moix

'La Scoperta del Fuoco', Santi Moix