interviews

Tatxo Benet: "I don't believe in the concept of self-censorship. If an artist is told not to wear a piece and he doesn't wear it, is that self-censorship?"

Tatxo Benet (Lleida, 1957) is a journalist and entrepreneur, managing partner of the Mediapro Group. He is also, since 2019, the owner of Llibreria Ona and in October of last year he opened the Museum of Prohibited Art in Casa Garriga Nogués, on Carrer Diputació de Barcelona.

The purchase at ARCO, shortly before it was not censored, of the work Political prisoners in contemporary Spain, by Santiago Sierra, was the genesis of its collection of censored art, which already has more than two hundreds of works censored, attacked, denounced or withdrawn from exhibition. Of these, forty-two are exhibited with excellent museography and a suggestive story. Among the works, a Picasso, a crucified Christ in an F-16 by Leon Ferrari, much criticized by the Pope, or Saddam Hussein by David Cerny.

Everyone tells him he's a collector. Do you have a passion for collecting?

To be a collector you have to be tidy, and I'm not very tidy. When I was young I collected trading cards and I remember collecting bus tickets from Lleida, but human beings have a passion for collecting more than anything. I have no idea when I got the urge to collect art. I wasn't aware of it. Maybe with the first posters I bought and hung in the room. I started buying things when I had the financial ability. At Christmas in Vinçon, he bought not very large works, by Júlia Montilla, Susana Solano or Santi Moix. There were people who bought Lladró, I bought Susana Solano. Then, since at home I like to be surrounded by things that attract me and have an artistic sense, I started buying more paintings, Plensa, Barceló... for personal enjoyment. And little by little you enter the world of contemporary art, you go to art fairs and buy, and that's how it went.

The genesis of the Museum of Prohibited Art is the purchase of Santiago Sierra's work dedicated to political prisoners?

Yes, but with nuances. I buy it before they censor it. I couldn't go there that year, but I saw the photos and the work interested me. I called a gallery owner at eight in the morning and asked to buy it. He did and after an hour they alerted me that it had been removed. At first I thought they were withdrawing it because I had bought it; then they explained to me that no, that it had been censored and removed. This did not automatically lead me to want to collect censored art, but it did lead to an interest in censorship issues. Shortly afterwards I decided to buy three works: Ines Doujak's sculpture of a sodomized King John Charles I, which led to the dismissal of the curators and the resignation of the director of the MACBA, and two bullfighting-themed photographs that had been censored by the Barcelona City Council, one in the Trias stage and the other in the Colau stage. And I started looking at things, but without any intention of making a museum. And I discovered Silence rouge et bleu, by Zoulikha Bouabdellach, which I really liked. It's a huge work, which you can't have at home, you have to have in a warehouse. What was the point for my personal collection? And since I had seen that there were a lot of them, of censored works, that was the moment when I decided that I would keep looking. And there it all started.

He found many.

And I was surprised how easy it is to find and acquire them. Censored works are like a bottle of champagne. They censor it, a great controversy is created, it appears in the newspapers for two days, they make those responsible resign and then they stop talking about it. And the artist has the piece at home and he himself does not want to take it out of the studio because, when he has an exhibition, everyone goes there for the piece and ignores the rest of the work. The works I bought were quite within reach.

In five years he has gathered more than two hundred works.

I was surprised that there was no collection, no museum, no gallery with this theme. Not even web pages dedicated to the subject. From here, the idea of doing something unique, of teaching these works, gradually emerged. First I thought of doing an exhibition, then we found this space and the idea became concrete. Finding Casa Garriga Nogués, where the Godia Foundation and the Mapfre Foundation had been, was definitive. And I rented the space three years ago.

Forty-two works are now on display.

yes The one for the political prisoners is in Lleida, because I transferred it before I thought we would make a museum, and it is in the Lleida Museum. We present these 42 works because the exhibition has a discourse, a meaning. We have another 170 plays that we'll have to show at some point, but we're in no rush. This exhibition has been around for quite some time.

It is a unique museum in the world. Did you like the reception?

I don't think it's a great idea. Museums are made of many things, chocolate, playing cards, everything. How could it be that no one had made a museum dedicated to censored, banned works? Even now I find it hard to believe that it is unique in the world, as far as we know. I think we would know right now. It has had so much repercussion on a global scale... It has appeared everywhere: newspapers, televisions, magazines all over the world. From Thailand, Malaysia, Turkey, Japan, the United States, Canada, Latin America, Africa. It's incredible. I work at Mediapro, where we make products on a global scale, movies and series, and I've never seen a press briefing like the one in the museum.

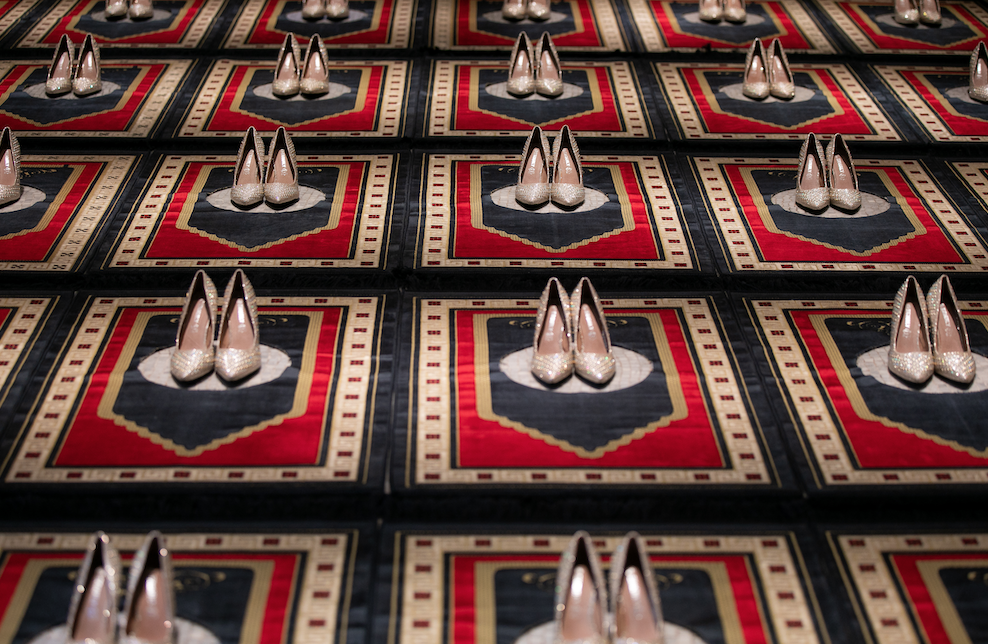

Zoulikha Bouabdellah. Silence rouge en bleu.

Zoulikha Bouabdellah. Silence rouge en bleu.

What is the most precious work or that has made you most excited to achieve?

I never know what to answer. But if one has a special meaning, it is Silence rouge en bleu, by Zoulikha Bouabdellah. Thirty Islamic prayer mats and thirty pairs of stilettos. A disturbing and beautiful work, which makes you reflect on the role of women in the Muslim religion. The City Council of Clichy decided not to exhibit it after the attacks on Charlie Hebdo and it was the first one I bought with the intention of making a collection of censored works. Also the Piss Christ, by Andres Serrano, where a photo is immersed in a container of the artist's urine. I found Zoulikha's work, but I consciously went to look for Andrés Serrano's because it is an iconic piece, which has suffered attacks. For Americans it is super iconic and so well known and so valued that I thought we couldn't get it. And when we acquired it, I was very happy.

He also opted for Goya's Caprichos.

It is the oldest we have. It was an impact, and as it stands I think it was successful. They are of the first impression, and when they were offered to me I thought they fell very far. But talking to the antiquarian and to people in the art world, I saw that the figure of Goya is modern and the story very interesting, and I decided to go ahead with the purchase because it brought prestige to the collection.

Is there censorship and self-censorship?

I don't believe in the concept of self-censorship. If an artist is told not to wear a piece and doesn't wear it, is that self-censorship? No, it's that someone said they don't want it. What should the artist do? Goya thought that with the change of government he would be sent to prison, he put the works away and left. When Zoulikha Bouabdellah was told by the mayor of Clichy and the Muslim associations that, after what had happened with Charlie Hebdo, look!, thinking that they could make her responsible for killing someone, she did not bring the work, but she she felt censored.

And has anyone pressured you?

no Nobody told me anything. It would never be censored here, because I have the final say on whether or not a painting is shown. And I assure you that will not happen. But no one has stood in my way.

The Museum of Forbidden Art is a private initiative. Has it had support from the institutions?

I don't know how to say it. Like opening a business. Warm relations, they have come to the inauguration, and it is a sign of support. No deal, neither for nor against. With the administrations I don't see what we can do, but with the city's museums, maybe yes. We are a bit of a rare piece. No one told me that it would help me, but neither that it would go against me.

Do you feel like a patron?

no In this matter, no. I understand a patron to be someone who sponsors an artist. I don't feel it and it sounds strange to be told that I am.

Looking for works to buy?

Yes, we have a list of ten or fifteen and we have to decide if we want to get them. We have it on hold a bit waiting to see how it all works out. The response has been very good, we have had a lot of people, international and local audiences. The museum is already another tourist attraction in the city. And with it we contribute to the deseasonalization of tourism.