reports

About censorship, cancellations, frictions, controversies and self-censorship

When we talk about censorship, we often think of prohibition or cancellation, of the knots that scandalized the Church in the past and that now continue to block the algorithms of Facebook and Instagram; in the criticism of religion, in Andrés Serrano's Piss Crist or in the political revolt of Pussy Riot. But history also shows us that there are more sibylline ways of making invisible what is important that it is not known. In the unpublished foreword to Animal Farm [The Rebellion of the Animals], George Orwell wrote that "unpopular ideas can be silenced and unpleasant facts concealed, without the need for any official prohibition." In our present overproduction of artistic and cultural proposals, it is easier to make invisible something that is not considered "appropriate" than to generate a great public gesture of denial that often ends up having an amplifying effect, the so-called Streisand effect.

Subversive memory

Sometimes, a cancellation can be the trigger for a new job. In 1988, TVE's cultural program par excellence, Metropolis, invited Antoni Muntadas to produce a new work. The artist explored for a couple of years the archives of TVE (key witness of the most recent history of the Spanish State), and found them in an absolute state of abandonment and neglect. He also observed that the visual rhetoric dedicated to King Juan Carlos I was not very different from that of Franco. With all this material, Muntadas delivered his TVE work: first attempt, a 40-minute video that the program never aired without explanation.

That situation, which the artist identified as a flagrant case of censorship, was the trigger for The file Room, (www.thefileroom.org), a work still active that collects cases of artistic and cultural censorship online, from from Ancient Greece to the present, and which is nourished by new incidents that users incorporate. The archive, originally produced by the Randolph Street Gallery in Chicago and the University of Illinois (Chicago), has since 2001 been hosted and maintained online by the National Coalition Against Censorship, based in the United States.

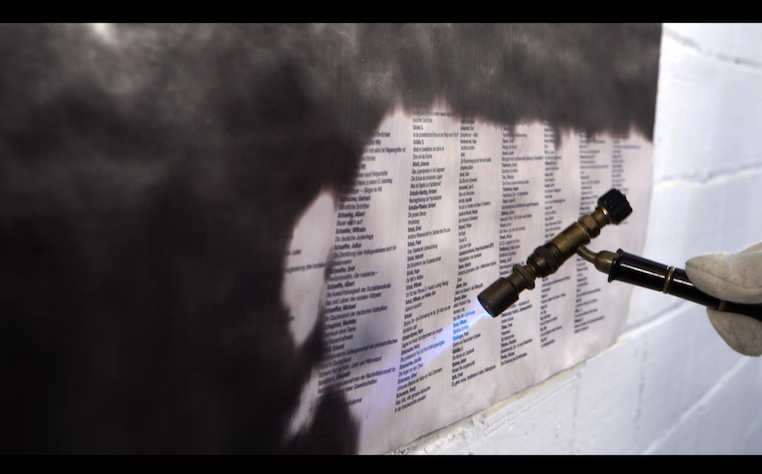

Miquel García, List of books burned in Germany in 1933. Obra gráfica: 226 x 138 cm. Impressió damunt paper, tècnica mixta. Vídeo: 6’24”. Barcelona, 2018.

Miquel García, List of books burned in Germany in 1933. Obra gráfica: 226 x 138 cm. Impressió damunt paper, tècnica mixta. Vídeo: 6’24”. Barcelona, 2018.

Readings against the norm

Books, as symbols of the generation of knowledge, have been (and are) subject to censorship, prohibition and burning. It was collected by Ray Bradbury in his dystopia Farenheit 451, which spoke of control, the banning of books and the fear of thinking for oneself. There are artists who reflect on it, such as Marta Minujín in The Parthenon of Books (literally, a Parthenon made of censored books, which was presented at Documenta 2017 in front of the Museu Fridericianum) or Miquel García (List of books burned in Germany in 1933, whose titles could be read precisely by applying a heat source; the fire that had made them disappear made them visible again).

Miquel García, List of books burned in Germany in 1933. Obra gráfica: 226 x 138 cm. Impressió damunt paper, tècnica mixta. Vídeo: 6’24”. Barcelona, 2018.

Miquel García, List of books burned in Germany in 1933. Obra gráfica: 226 x 138 cm. Impressió damunt paper, tècnica mixta. Vídeo: 6’24”. Barcelona, 2018.

Censorship frictions

There are artists who do not work directly on censorship as a subject but who delve into issues that create friction. This is the case of Núria Güell, when she explores aspects related to financing (in Arte político degenerado, protocolo ético, 2014, she created, together with Levi Orta, a limited company in a tax haven, with the production money of a center of public art, and some time later he gave the management of the company with all its advantages to a group of activists who were developing a project of an autonomous society at the margin of capitalist dynamics); with the working conditions of the artists (in Afrodita, in 2017, the production budget of an exhibition was used to pay Social Security contributions for seven months, in order to be able to collect the benefits during her maternity leave), and with the reintegration of prisoners (Human resources, 2022, in which German prisoners could access a job but, being in a cultural institution, it could not be remunerated but compensated in the form of an invitation to lunch pizza and Fanta).

Miquel García, List of books burned in Germany in 1933. Obra gráfica: 226 x 138 cm. Impressió damunt paper, tècnica mixta. Vídeo: 6’24”. Barcelona, 2018.

Miquel García, List of books burned in Germany in 1933. Obra gráfica: 226 x 138 cm. Impressió damunt paper, tècnica mixta. Vídeo: 6’24”. Barcelona, 2018.

Self-censorship and other controversies

Other artists, such as Santiago Sierra, use controversy as a creative tool to generate a loudspeaker effect from their works. Sierra delves into very critical issues and does so from stories, which already in their titles, generate controversy: Muro de 137,400 liters de agua del Mediterráneo, 2022; National coat of arms of Spain stamped in blood, 12/10/2021; No (King of Spain), 2019; Political prisoners in contemporary Spain, 2018; 697 state crimes, 2018; Afghanistan war veteran facing the wall, 2011; Burial of ten workers, 2010; among others

But undoubtedly the worst censorship, the most effective, is self-censorship, the fear of saying or doing what is not appropriate, that may not be liked, that may be uncomfortable, that is not politically correct or that may be the object of criticism in the public sphere, that is, in social networks. The artist Ragnar Kjartansson spoke against self-censorship in the documentary Soviet Barbara, the Story of Ragnar Kjartansoon in Moscow: "I have exhibited in politically questionable places, because I think it is better to do something subversive than not to do it."