reports

The dumbed down story. Feminine art to make the silences speak

They always have been. And not only as muses, helpers, mothers and wives. Not only as companions of another's creative process, but as producers and creators of a knowledge and a valuable artistic experience that has been muted and spared over the centuries by a patriarchal system. The will to claim the female legacy, from a broad perspective of gender and genres, is to complete the other half of an artistic narrative that becomes biased and partial without their presence.

The presence of women in art has been spared over the centuries by a patriarchal society that has made women the accomplice par excellence of nature and its procreative work. In fact, the revolution of the female sex in the 21st century is shaping the real social change of this century.

In 1949, Simone de Beauvoir published the book The Second Sex, in which she states that "you are not born a woman, but you become one". In art, the presence of women has been frankly scanty until today, in which the will to act from a perspective of gender and genres, in the plural, has opened the doors to an activist message in favor of freedom sexual and the right of women to decide their destiny in this world. And artistic creation is one of these fields of freedom that women can achieve today, not without difficulties.

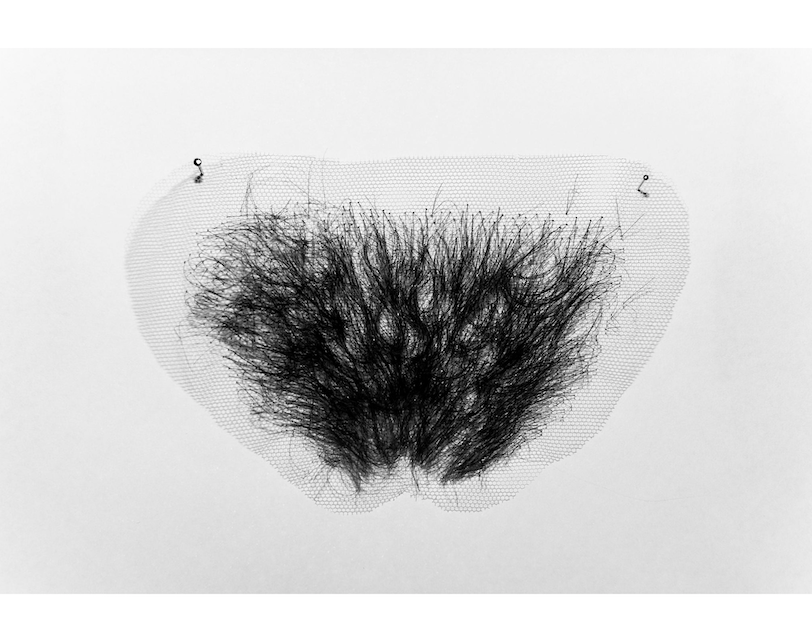

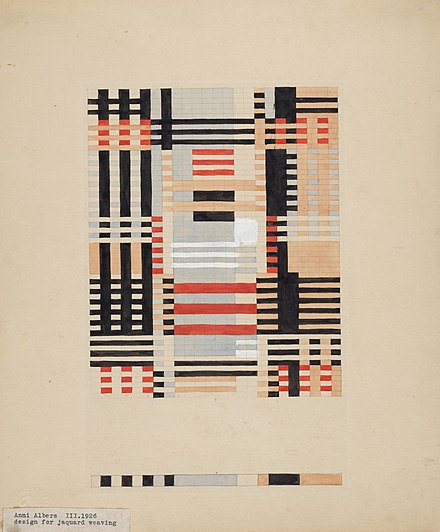

Anni Albers. Design for a Jacquard Weaving, 1926

Anni Albers. Design for a Jacquard Weaving, 1926

Neither muses nor submissives

At the turn of the 19th century, the image of women in art embodied the prostitute, the model or, in the case of the bourgeoisie, women were seen from a melancholy perspective, also associated with hysteria and mental illness. There were few women who, with the wealth of their families, could train in painting, sculpture or music. Some were collaborators or models of an artist, such as Camille Claudel, who eventually broke away from August Rodin to pursue her own work as a sculptor, but paid for it with nervous breakdowns and with the internally the last thirty years of his life in the Montdevergues asylum.

Surrealism maintained an ambivalent attitude. On the one hand, the woman was the muse, the inspirer of the colleague's work, but on the other, mental illness was recognized and accepted as a field of creation, a fact that allowed off-the-record romances such as that André Breton held with Nadja through the streets of Paris. It also allowed some mentally ill women to excel in art, such as Unica Zürn, despite being Hans Bellmer's doll. Women artists such as Remedios Varo or Leonora Carrington, who surpassed their colleagues Benjamín Péret and Max Ernst, respectively, leave the ordinary level. And we could add Kay Sage, partner of Yves Tanguy; Jacqueline Lambda, by André Breton; the photographer and artist Lee Miller, wife of Roland Penrose, without forgetting Frida Kahlo, the great Mexican female myth linked to surrealism and wife of Diego Rivera. The European avant-garde gave names such as Hannah Höch, within Dadaism, or Sonia Delaunay, within simultaneous cubism, and Sophia Tauber-Arp, within a constructive abstraction. And this without entering the field of design from the perspective of the Bauhaus, where we would find quite a few female names alongside Annie Albers, wife of Joseph Albers. As we see, most women are partners of other artists.

Feminist Catalonia

In Catalonia, a book published by Elina Norandi in Enciclopèdia Catalana attests to 102 women artists who have produced quality work despite the difficulties that their female status entailed. Some have been rediscovered very recently. Art criticism of the time, written by men, focused more on the beauty of the women painters than on the pictures, and descendants have often barely kept the works of a single painter aunt they did not know or have taken the paintings to Encants. It is a typical and clichéd example of what has happened to women artists. Of the different periods, it is worth mentioning within modernism Lluïsa Vidal (1876-1918); Laura Albéniz (1890-1944), daughter of the composer Albéniz; the Polish Mela Muter (1876-1967), first professional Jewish painter during her time in Barcelona; the surrealists Remedios Varo (1908,1963), who was born in Catalonia but ended his life in Mexico, and Angeles Santos (1911-2013), partner of the painter Emili Grau Sala who, after a brief foray into surrealism, return to a resounding representation in which the female figure is very present. The door opened by surrealism allows the creative alienation of Josefa Tolrà (1880-1959) to be recovered, and the refuge that some artists find in Barcelona during the First World War keeps Olga Sacharoof (1881-1967) staying to live in city

Lola Anglada stands out in the panorama of the noucentisme, whose morals leave the woman the role of mother, educator and in charge of household chores. Later, during the post-war period, Maria Girona, within a Mediterranean post-noucentism, and Amèlia Riera, who claimed the sexual freedom of women in the sixties, would stand out. We must add those who renew textile art, such as Aurèlia Muñoz and Maria Assumpció Raventós; abstract painters like Carme Aguadé or Elena Paredes, and painters of a certain magic, like Magda Bolumar.

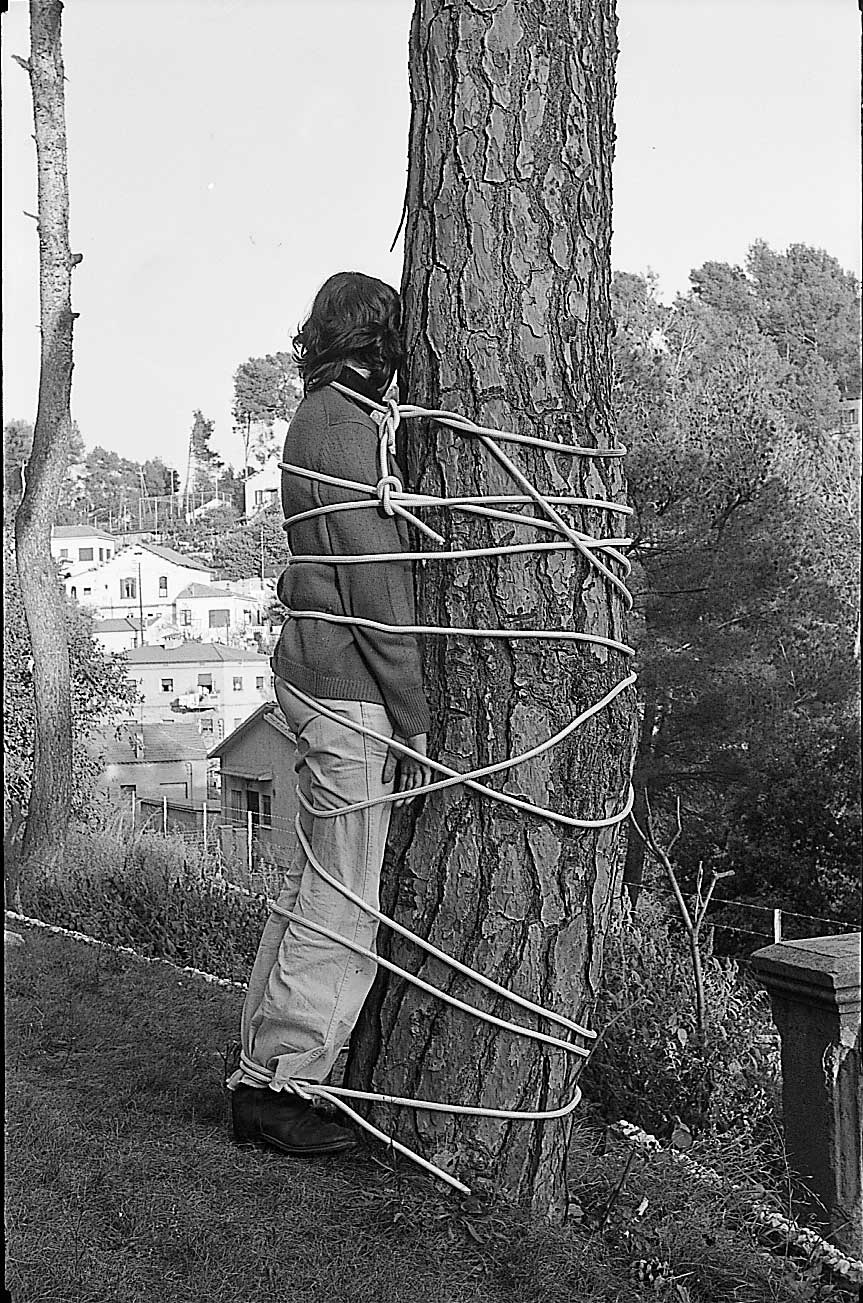

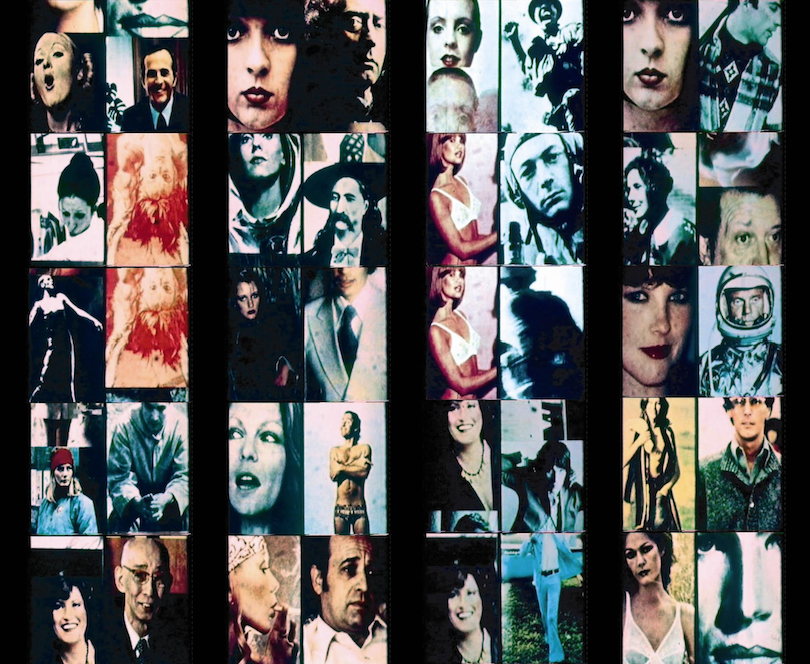

Eugenia Balcells. Boy Meets Girl, 1978

Eugenia Balcells. Boy Meets Girl, 1978

The vindication of gender

The generation of the seventies opens the doors to performance and the vindication of the genre beyond artistic practice: Fina Miralles, Eulàlia Grau, Sílvia Gubern, Àngels Ribé, Eugènia Balcells, Dorothée Selz, Olga L. Pijuán, a generation that will find heirs in the eighties such as Susana Solano, Mari Chordà, Marga Ximénez, Margarita Andreu or Kima Guitart. An essential book to become aware of the female creative universe that the plastic arts have left and are leaving in Catalonia in the 21st century. Pilar Parcerisas