Exhibitions

The Queen Sofia Museum presents 'Picasso 1906. The great transformation'

On the occasion of the commemoration of the 50th anniversary of Picasso's death, the Reina Sofia Museum is organizing the exhibition 'Picasso 1906. The great transformation' in collaboration with the Musée Picasso Paris

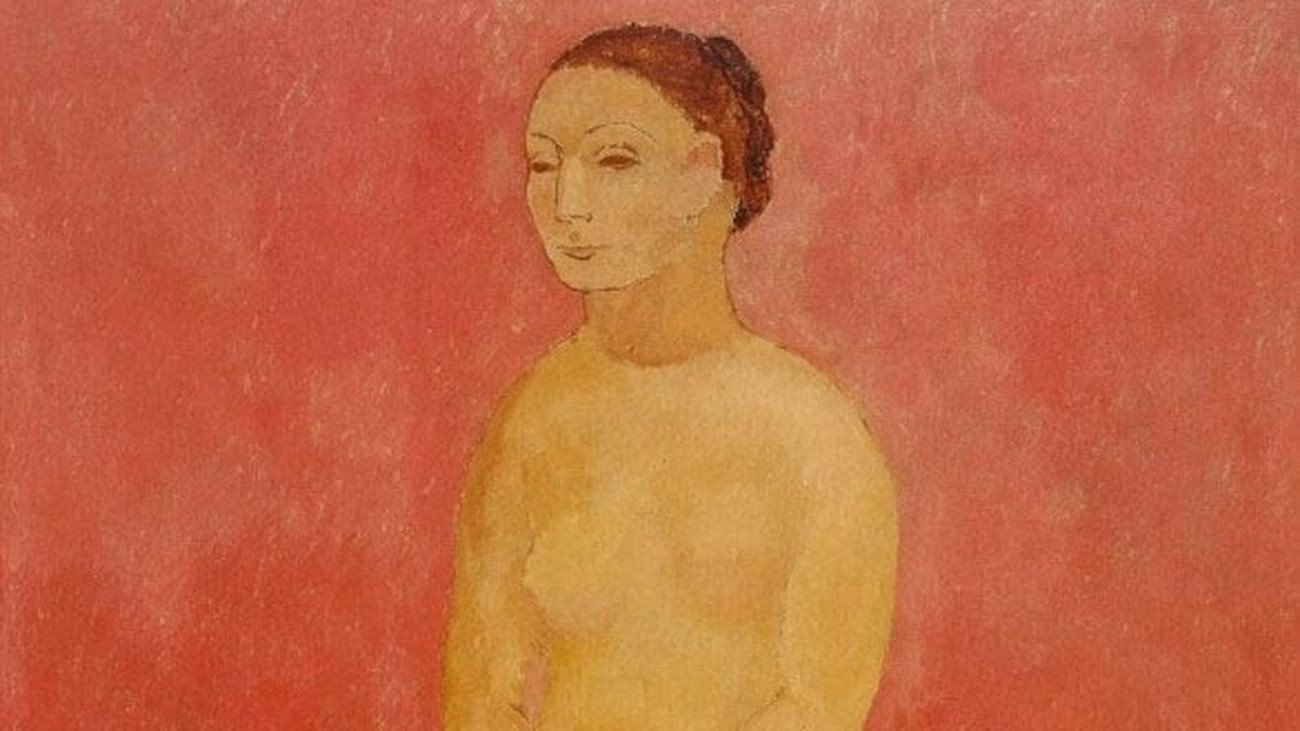

Picasso 1906. The great transformation, which can be visited from November 15 to March 4, 2024, wants to look, from a contemporary aesthetic awareness, at the artist's first contribution to the definition of modern art. Until now, Picasso's production in 1906 has been understood as an epilogue to the pink period or as a prologue to Las señoritas de Avignon. But today it can be said that 1906 was a "period" with its own entity in Picasso's creative development. At only 25 years old, in 1906, Picasso is still a young artist, but already mature in his aesthetic criteria. Leaving bohemia and pessimism behind, it is vital and expansive, even sensual; he approaches libertarian approaches and longs for the refounding of the artistic experience.

With the support of dealers and collectors, and related to a powerful group of contemporary creators, he lives dedicated to the "processual" sense of his work, seeks "the primordial" and develops his work in three registers: the body, the form and interculturality. Picasso approaches the representation of Arcadian adolescence as a symbol of a new beginning.

The painted body assumes its own emancipation. The artist bluntly addresses the power of the scopic drive in its relationship with the unawakened female intimacy. What is vernacular is posed as a mythology of origin. The figurative imprint of Fernande Olivier, his partner at the moment, is used as a support for the experimentation of plastic languages. The Málaga artist is able to generate generic facial expressions and bring them to the quality of a synthetic ideogram.

At the same time, he redefines the framework between background and figure, proposes a new sense of mimesis, and develops material and tactile concepts in the modeling of sculpture. His accelerated pace of transformations will culminate in the first two months of 1907 and, in all his overflowing activity, for him, the dialogue with Gertrude Stein was for him crucial.

In the search for what is primordial, the artist proposed a full synergy with the artistic productions of cultures then considered "primitive". This phenomenon, turned into a poetics, occurred in 1906 - and not in 1907 as has been supposed - and did not represent the fixation of a particular model, but rather an effort at hybridization with which to place something equivalent to a "common language" of the primordial. Picasso's cultural references, in addition to Iberian art and the so-called Negro art, spanned the Catalan Romanesque, protohistoric Mediterranean art and ancient Egyptian, among others.

References that Picasso assumed - as he explained himself - not as mere formal data but as active and non-alienated cultural presences, framed in collective rituals and endowed with a powerful capacity to relate to the transcendent. And you need to understand this way of doing things well. Sometimes it is the artist's work itself that brings him to the encounter with "the primitive". And, sometimes, it is "the primitive" that inspires him. It is a dialectical relationship.

Picasso's interculturality can also be understood from other parameters. The artist's biography itself incorporated powerful experiential displacements. Picasso was aware of "the otherness" of gender. He captured homoerotic and ethnographic photography in a peculiar way. He raised new anthropometric molds. Or he used the mass press and picture books at work.

In his way of understanding visual memory, he undermined the idea of anachronism and kept the heritage of Art History underlying, using quotation and appropriation with an almost contemporary sense. And it was this complex relationship between cultures, primordial language and museum memory that made the Picasso of 1906 unique and marked his first decisive encounter with modern art.