Exhibitions

Mederic Turay A dream that doesn't stop

Out of Africa Gallery presents, from September 23 to October 22, the individual exhibition of the artist Mederic.

He has more than 40,000 followers on Instagram, only 75 posts and some with 5,000 likes; he also has a YouTube channel, where you can see videos of his exhibitions, painting graffiti, advertising a beer advertisement wearing one of his shirts, which he designs himself with his personal iconography and that some of the his privileged collectors already own, or himself dancing with spectacular grace and rhythm; it is clear that he is one of the young artists of the moment. He is Mederic Turay (Côte d'Ivoire, 1979), who in 1999 was elected Best Young Artist of West Africa. His love of art began as a child; at the age of 4 he was already drawing imitating cartoon characters and works by Picasso, Dalí and Basquiat. He grew up immersed in American urban culture, since his father, a professional soldier, accepted a mission in Washington; it was 1984, so Mederic lived in America the golden era of hip-hop (the so-called "Hip Hop Golden Era"), living the dance as a body expression, singing rap and painting graffiti, a whole cultural explosion which clearly influenced the natural evolution of his work. In 1995 his family returned to Ivory Coast, Mederic then began his Fine Arts studies and found the roots of his culture, which have been manifested through his art. These two worlds, which are part of his life experience, coexist in perfect harmony in his work. He is convinced that life transformed him into an artist because he believes that art remains the greatest expression of life. One of his mottos is: "be inspired to follow your dreams, then nothing can stop you". It is represented in such important collections as that of Charles Saatchi, that of the King of Morocco, Mohamed VI, and the Niarchos of Switzerland.

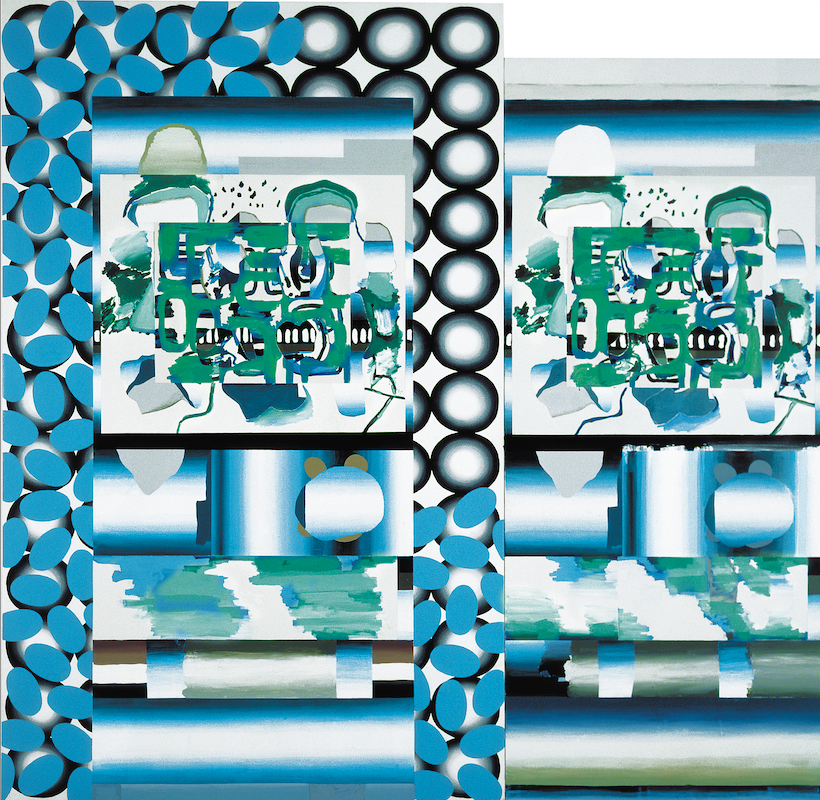

At the outset, his painting is attractive due to its exuberant color that seizes the gaze, a gaze that cannot stop because, beyond the color, it is trapped by a labyrinthine "horror vacui", which forces you to go through the entire the fabric and that it can become a metaphor for a quantum universe where everything is connected, that is to say, it becomes a metaphor for reality, a reality that we don't always see. His paintings are like treasure maps where there is much to discover. He says that he paints the noise that surrounds him and that he creates his own inner landscape because when he paints he is guided by a need to occupy the entire canvas without stopping. I believe that this "feeling guided" corresponds to the inner strength, to the creative impulse that Carl Gustav Jung spoke of when, in his phenomenology of the creative process, he discovered the "autonomous complex", which he defined as a splintered portion of the psyche that leads a life of its own outside the hierarchy of consciousness; therefore, the creative process has a conscious part, which is the intention, and another, of an unconscious nature. With this impulse to paint without stopping, Mederic creates a territory that connects his multiple experiences, his own and collective, various cultures, urban art and primitive art, his own influences as an artist, past and present, life and death , showing the opposites as indissoluble parts of the unit, as happens in reality and the Universe.

Mederic plays with the distortion of the form, with the relationship between the figure and the background, with the gradient of size to suggest depth without resorting to perspective, with the impact of color and with collage, with which he introduces the stability of the concrete in an abstract scenario. All his characters appear crowned; for Mederic, who confesses to having a strong belief in the presence of crowns around a living being, be it human or animal, he interprets it as the manifestation of what we radiate on others, on the world, which he would describe as the 'aura, a fact that introduces us to the world of the spiritual. The collages of early African art sculptures coexist with their abstract human and animalistic representations; they are smaller, as if they are further away in space and time but, in reality, they represent the past in the present because neither time nor its becoming is linear. Formally, these collages for Mederic are a way of playing with fullness and emptiness, with realism and abstraction and, conceptually, it is a way of creating a link between spirits and men, connecting the invisible with the visible This desire to ascend to the world of the invisible explains the large presence of masks in his paintings, since in African religious rituals, masks have the function of representing the supernatural.

The characters that occupy his canvases, radiating with their aura and their vibration all around them, have different and powerful looks, as an example of a non-verbal language; they are eyes with X crosses, with dots, with iridescent circles, in coffee beans, with swirls of light, as an expression of different messages. Looking at the viewer and in all directions. With his characters, Mederic wants to evoke life and death at the same time, because he believes that it is the intensity of self-awareness, the definitive character of self-discovery that prepares and enables the "timeless" of death. And he has a poetic vision of life and death: "Little deaths are fragmented throughout our lives. The same abyss widens, the same vertigo is horrified by the evocation of one and the other . Self and death are twin mirrors. With the veil removed, they meet in a kind of incestuous embrace. The resulting destruction is not necessarily only physical death, it is also mental death, hallucination and madness, a picture of spiritual death." It is like thinking of death, on this earth, as a step to another plane with an awakening of consciousness; so Mederic with his painting traces an arc that could go from the sun disks of the African cave paintings to more metaphysical, philosophical and spiritual questions.

His painting is endowed with an interesting conceptual and philosophical charge about the invisible world; this world which, despite being there, is not easily perceptible, so it turns to primitive art as the first representation of man and animal in all their authenticity since the caveman. These totemic presences – the ones he applies with collage – act here as a revisitation of traditional African religions with their totems, beings so magical and so powerful that they are able to create links between animals or plants and groups or individuals of a clan. Mederic does not stop seeing the two sides of the same reality and these totemic presences in his paintings are like part of the witnesses of time, they tell the story with himself; they are the representation of the primitive spirit, a memory of their ancestors, of traditions, and their works are inspired by African fables or poetry, which bring the sacred to their contemporary creation.

His work is rich in meaning because it tries to address the complexity of what is human through our evolutionary and cultural history; for this reason, his paintings are populated with numerous human references with characters that carry in themselves their personal history, such as joy, sadness or love, common emotions and feelings, but lived in different ways in a world that we still don't quite understand.

Along with the contemporary spirit of his painting, Mederic is very much aware of "Alkebulan", as his ancestors called Africa, which means "Garden of Eden" or "Mother of mankind", and recognizes that Alkebulan, as search for the origin of humanity, is an eternal source of inspiration for him as an artist. Years ago I studied the amazing cave paintings of Tassili in the Sahara desert. It is still a mystery which civilization could have painted them some 10,000 years ago -12,000, according to the sources-: enigmatic human representations, boats, hippopotamuses, rhinoceroses, animals that need a lot of water to live; the probability is so great, that it is believed that they could not have painted them like that if it had not been because they could see them there. Africa was then a green paradise, with abundant rivers and lakes, comparable to the idea we have of the Garden of Eden. I asked Mederic if he knows Tassili; he has not seen them in nature either, but he has visited the cave paintings in Morocco, those of Oukaïmeden in Marrakesh during his giant installations in the mountains, which he remembers as a very pleasant experience and something very inspiring for his work

With a retrospective look, I connect with the philosophy of historical Romanticism and with their awareness of the human feeling of fragmentation, which led them to the search for the reconciliation of opposites, a longing that became one of the pillars of André's Surrealism Breton with a tireless and deep investigation of the inner world; it was Carl Gustav Jung who came to resolve this conflict through the collective unconscious also connecting it with quantum physics. For this reason, I would dare to trace a bridge between Mederic's labyrinthine maps, where a link with the collective unconscious can be perceived through these totemic figures and African fables, up to historical Romanticism, arriving- there step by step and saving the distances.

At Mederic's request, I end the text with a quote from a great African writer and thinker, defender of the oral tradition and known as the "wise man of Africa", Amadou Hampâté Bâ (1900-1991): "In Africa, when an old man dies, a library burns."