Opinion

Architecture and society: an impossible dialogue?

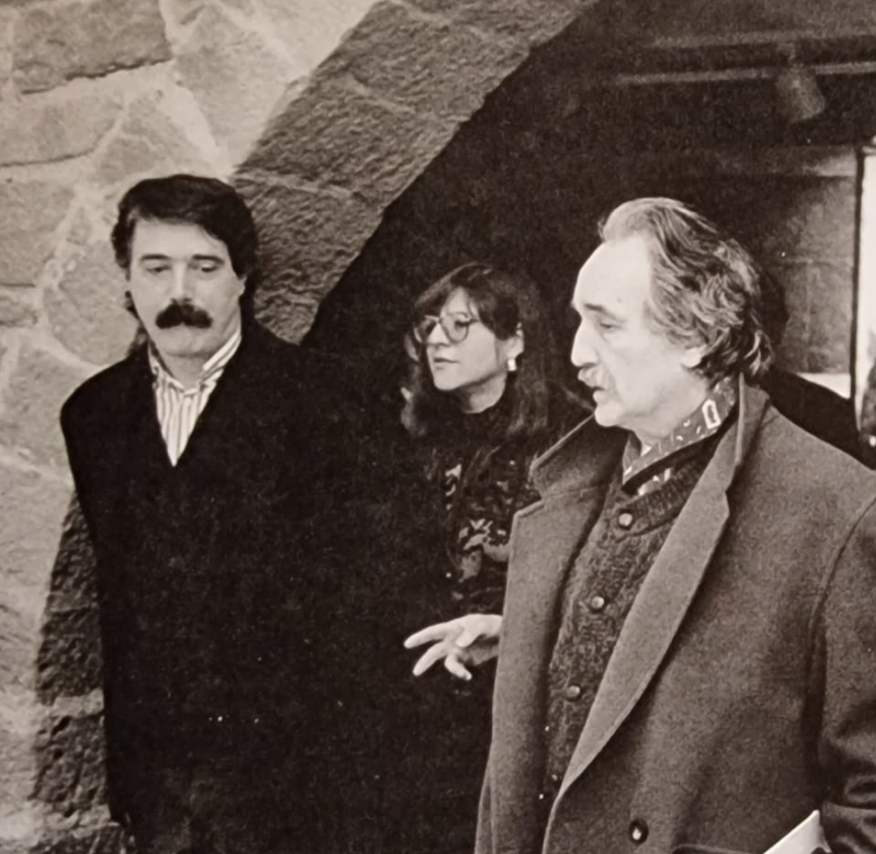

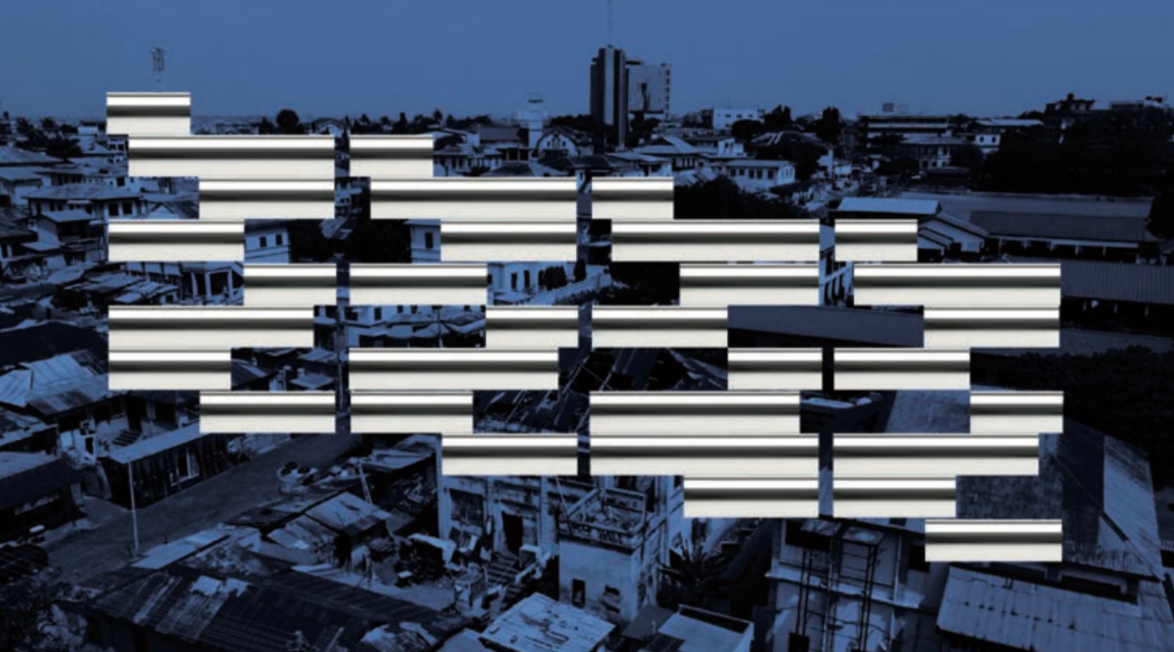

The coincidence of this topic with the Catalan participation in the Venice Biennale in 2023 is not an improvisation. It is true that this Biennale, a true global showcase of the situation of architecture and urban planning in today's digital and global world, has fulfilled its role with flying colours. The Milan Triennale was also celebrated when in 1994 Professor Paul Ricoeur published an article on architecture that went around the world. The topic proposed in Venice this year on the scenarios of the future already has a very interesting and, as always, controversial answer, because that is what it is all about: opening up the topic with debates of global interest.

If the biennials do their job well, perhaps those who do not do it so well, in relation to the dialogue between architecture and society, are governments and political forces. Arguing this in a page of text is an impossible task, but I will try in a very, very, synthesized way.

Challenges for the success of the dialogue

Why does a socially useful dialogue about architecture and society cost so much? A first answer is because we don't have the laws ready to make it useful. The article I just mentioned by Paul Ricoeur made it very clear: the projects and plans of architects and urban planners must be grounded in the day-to-day lives of the users of each place that is intended to be changed. For this to be possible, dialogue between the different estates is necessary and this, for example, requires a clear law of incompatibility between estates and people that supports mutual trust.

If the politicians responsible for giving the building permits have relations with the project manager or with those responsible for the construction of the building or the city, this does not look good and the dialogue cannot work well. If the users and owners of a project suspect that the project is modified by ties between the project managers and the political power, this does not seem correct either. Finally, if reports on the impact and suitability of projects and plans are made by the same experts working for the permitting body, or for friends, partners or acquaintances of them, this cannot work well .

Review the benefits

It is clear that this difficulty in the dialogue between architecture and society has a strong economic and political component. It has always been like this, and that is why those who drew up the constitution in the classical era of the city of Athens went on a three-year trip so as not to have incompatibilities of any kind and when they returned, if necessary, the constitution was changed in view of practice. That is why it is well known that the percentage of individual or family wages that finance where you live to have a decent home, is a good indicator. And it is a promise that is in the constitutions of the cities but that is rarely fulfilled. If this percentage is greater than 30, it means that there is abuse in the distribution of benefits in relation to the affected people.

The covid has increased interest in this relationship, hopefully for good. Several magazines in South America, in Argentina and Chile, and others in France, have launched monographic issues - as Bonart magazine has done in Catalonia - and this is a good sign of worldwide interest. But until the interest comes to the new laws that I have said are necessary, we may have to wait many years.

"Where's the fire?"

What I want to say is that the dialogue between architecture and society needs a high level of democracy to be effective; otherwise, with all the good will in the world, the result is a growing lack of communication and a lot of misunderstandings, as in the always difficult problem of "subsidized" housing, of sad memory.

It is obvious that education is fundamental here. And I can't help but refer to the topic of architecture education since childhood, and nothing better than being able to relate an experience with my 28-month-old grandson. One day, very seriously, and looking into my eyes, he asked me: "Where is the fire?" And hours later he told me: "Television is everywhere." He hardly speaks, but he's not bad for a start. Of course, these words referred to my intention to teach him how to light a fire, which is always dangerous, and to the fact that the family does not want him to be watching TV all day, as he wishes. Where the fire is, really, no one knows, and the fact that television is in more and more places is because of our will. But this asymmetrical spatial situation worries my son. We hope that he will never lose his curiosity and, thus, maybe he will be able to find out where the fire is beyond the unknown origin of the universe, wherever the so-called artificial intelligence wants to lead us. Yesterday, a robot, in La Vanguardia , answered the question of who it was by saying that it was "a man". It was a wrong answer, because it was a machine. My nephew would disagree with the answer.

Laboratory of the future. Courtesy of the Venice Biennale. ©Fred Swart.