Opinion

Dalí vs. Nietzsche: a mustachioed question

"The one thing the world will never tire of is exaggeration"

Salvador Dalí

The written work of Salvador Dalí has remained undervalued for many years, but it is through it that the genius from Emporda provides many of the keys to understanding his art and his "philosophy of life". One of these keys is the influence that Friedrich Nietzsche had on him, a subject that has not been studied in depth until now. Only Robert Radford explored the surface of this relationship in his article: "'Nietzsche aside, you won't find anyone like me': reflections on the mythic structures that shape Dalí's project of self-realization". However, neither Radford in his article, nor Carmen García de la Rasilla, nor Pedro Alonso García, in his monographs on the artist's autobiography, delved too deeply into the relationship between Dalí and Nietzsche. Taking a Nietzschean perspective will shed new light on a field still dominated by the influence that figures such as Freud, Lorca or Breton had on the Empordà genius, thus contributing to a more multifaceted conception of his person.

Dalí referred to Nietzsche, on multiple occasions, as the only man with whom he could be compared: both shared an approach to life in which the affirmation and integration of chance allowed them to go beyond the morality and truth, always moving forward in his existential ambition despite any impediment. In an interview with the German magazine Pardon in February 1975, Dalí declared that he had successfully embodied "the absolute superman". The painter from Figueres can therefore be considered a case study that allows us to analyze the ideal of the superman through someone who self-determined as such. As shown in Diario de un genio , Dalí even expresses his intention to surpass the creator of this concept:

"Even in mustaches I was going to surpass Nietzsche! Mine would not be depressing, catastrophic, full of Wagnerian music and fog. They would be sharp, imperialist, ultra-rationalist and would point towards the sky, like vertical mysticism, like the Spanish vertical unions ."

Reading Dalí's autobiographical texts as fiction, we approach what Nietzsche described as a “justified lie” designed to endure the pains of existence. In this way you can see how the surrealist artist tried to make a work of art from his life, and therefore from his narrative. In The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí, his 1942 autobiography, he describes how, as a child, he looked through the books in his father's library and how he was greatly impressed by Voltaire's Dictionnaire Philosophique , or how Kant must have been an angel to be able to write such important and useless books, the reading of which filled him with pride and satisfaction. But when he read Thus Spoke Zarathustra , he thought he could do better. Twenty-two years later, in his Diario de un genio , Dalí recalls how he first met the prophet of the superman:

"Zarathustra seemed to me a fabulous hero, whose greatness of soul I admired, but at the same time he was known for some childishness that I, Dalí, had long since overcome. There would come a day when I would have to be greater what he! The day I started reading Thus spoke Zarathustra , I already formed my concept of Nietzsche. He was a weak man, who had the weakness to go crazy! These reflections provided me with the elements of my first slogan, the one that , as time went by, it would eventually become the motto of my life: 'The only difference between a crazy person and me is that I'm not crazy!' "

To what extent did Dalí surpass Nietzsche's Zarathustra? Could it be said that this existential effort became a recurring leitmotif for him? These questions can be answered in a careful reading of each of his four autobiographical texts: Diary of 1919-20 (1920), The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí (1942) and Diary of a Genius (1963), as well as the his highly autobiographical roman à clef Rostres ocults (1944), his interviews, paintings, performances, ballets, etc.

The competitive relationship that Dalí had with Nietzsche can serve as a source of tears for many aspects of the life and cosmogony of the artist from Emporda, in the same way that the concepts developed in critical texts about the German philosopher can illuminate some of the passages of 'more exaggerated self-assertion by both authors. Half ironically, half seriously, in one of these passages in Diario de un genio Dalí considered that he had surpassed both Proust and Nietzsche, at least in the matter of moustaches:

"I am sure that my abilities as an analyst and psychologist are superior to those of Marcel Proust. Not only because I use psychoanalysis, which is one of the many methods that Proust did not know, but, above all, because the structure of my spirit is of an eminently paranoid type and, therefore, the most suitable for this class of exercises, while the structure of Proust's is that of a depressed neurotic, that is to say, the least appropriate for his investigations. Easy to guess and deduce from depressing and distracted style of his mustaches, which, like Nietzsche's, even more depressing, are diametrically opposed to those of Velázquez's cheerful and lively drunkards, or, even better, of the ultra-rhinoceros of your genial and humble servant."

Dalí liked to present himself as a "Freudian hero", since he considered himself to have overcome all the traumas and complexes diagnosed by psychoanalysis, and this allowed him to place himself above Proust, who is, in fact, the reference of 'a Nietzschean literary life according to Alexander Nehamas. Although Dalí agrees with Nietzsche that traditional morality has challenging consequences for humanity, he needs to use Freud's theories as a reference to free himself from the tyranny of the subconscious – especially his superego.

Dalí was not alone when he highlighted his resemblance to Nietzsche's superman; in the introduction to Confessions inconfessables (1973), the biographical book based on interviews made by André Parinaud, this French journalist states that, if Nietzsche had met Dalí, he would have seen in him his superman, because of his will to power , his continuous self-improvement, his great lucidity and his permanent defiance of death, morality, the establishment and men. But beyond exploring Dalí's competitive and megalomaniacal obsession with Nietzsche, it is also interesting to try to redefine the elusive idea of "superman" in direct contrast to the surrealist artist, a fact that can contribute to the current debate on post-humanism .

If the Nietzschean intuition of the eternal return is taken as a reference, each moment must be accepted and life affirmed as a whole. Dalí does this through his autobiography, indicating for example in La vida secreta, that he is responsible for every detail narrated in it, thus making everything work in his favor. This tragic understanding of existence, whereby one is willing to constantly integrate chance, is very close to the Nietzschean ideal of making a work of art out of one's life. In order to understand the mechanisms of this "aesthetics of existence", I propose a reading of Dalí through three major themes and authors:

Statement: Zarathustra's throwing of dice and the logic of chance (Deleuze – Nietzsche and philosophy ).

Integration: Proust and the autobiographical accumulation through literature (Nehamas – Nietzsche: Life as Literature ).

Generosity: Self-praise and the morality of selfishness (Sloterdijk – On the improvement of the new. The fifth “Gospel” according to Nietzsche ).

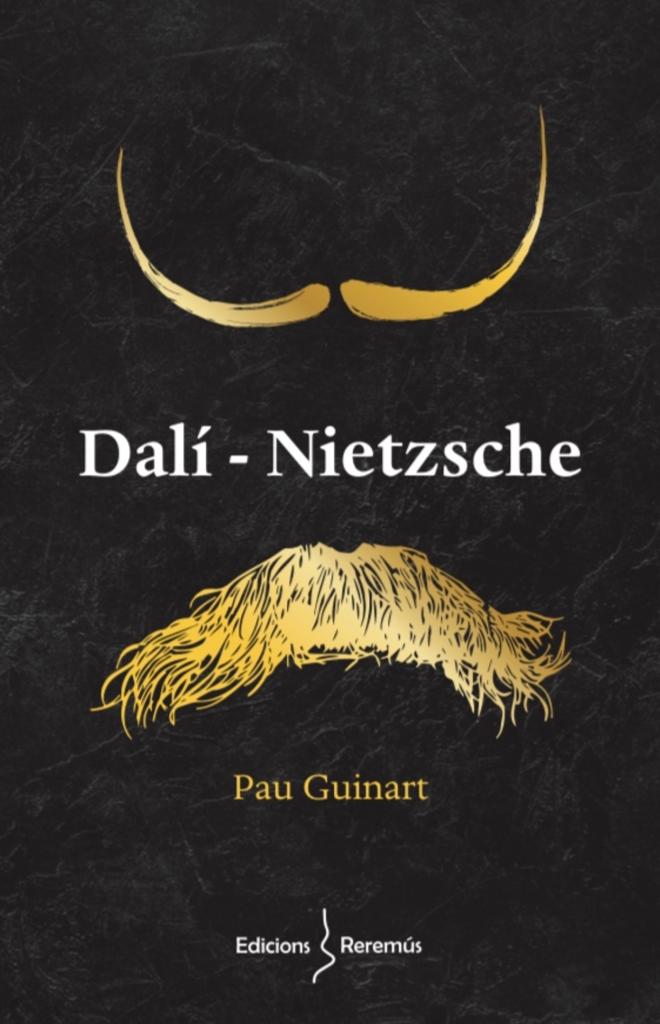

These three concepts, widely deployed in my book Dalí – Nietzsche, can be of great use in understanding the artist's life. But, after all, the question around which all the others revolve would be the following: What is the most intense and authentic life possible? As an answer, Dalí's case can be used to explore, first, how intense and authentic a life can become, and second, to what extent one can be justified in asserting that one is on a higher level of 'humanity. An approach to Dalí's life through Nietzsche offers precisely the opportunity to do this, and also to understand both as φαρμακοι ( φαρμακοι ), that is: poison and remedy (in addition to scapegoat, in the sense Derrida gives it). As soon as they can be healers when used in the right amount, just like dynamite, (Nietzsche: "I'm not a man, I'm dynamite"), or drugs (Dalí: "I don't take drugs, I'm the drug"), they can be dangerous to treat. This unpredictability of care, this risky thinking, which can lead to great benefits (and also losses), is what makes these two characters so fascinating, and at the same time repulsive... but above all, imaginatively fertile and existentially stimulating.

More information on this topic can be found in the book Dalí – Nietzsche. Theory and practice of human improvement (Edicions del Reremús, 2022) , based on the doctoral thesis defended at Stanford University: Outdoing Zarathustra: Salvador Dalí's Rendering of Nietzsche's Übermensch.