library

Four conceptual revolutions

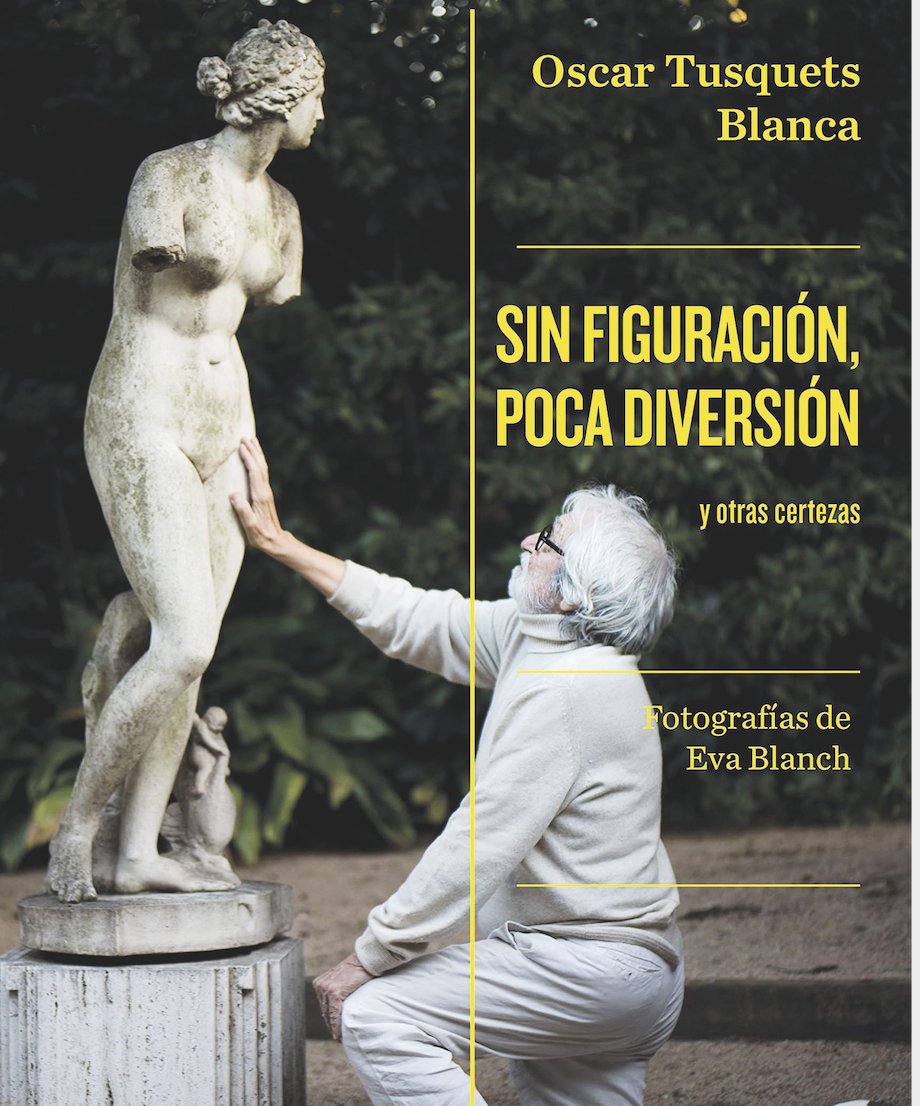

There is no more titanic task than having to write a unitary text about four seemingly disconnected books. Only the craft of criticism can come to an enterprise like this, that of finding the common thread of four works published at different times and on seemingly distant themes even though they are included in the category of art. From Bonart I am being asked for the joint review of four wonders: Pinturas , by Óscar Astromujoff with madhouse poems by Leopoldo María Panero (Ambit); What we don't see, what art sees , by Graciela Speranza (Anagrama); Sin figuración, poca diversion , by Óscar Tusquets Blanca (Tusquets), and Maternasis , by Núria Pompeia (Kairós). Beyond the fact that two of the authors are named Oscar, there doesn't seem to be any kinship, does it? Well, let's go, because there is a concept that ties all four of them together: the artistic revolution, the novelty, the transgression and, why not, the discomfort of the spectator.

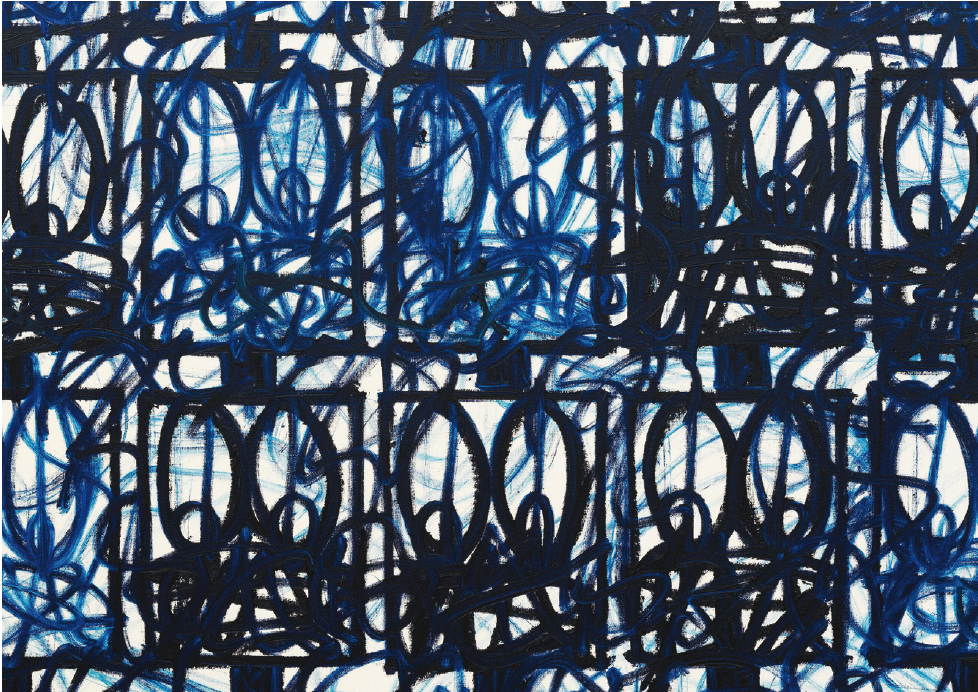

Núria Pompeia's catalog book is a cult book and icon of feminism published for the first time in 1967 and which represented a double revolution both in the field of graphic design and in the point of view on motherhood. Between Zen aesthetics and counterculture, Pompeia knows how to convey the bag of emotions that a pregnancy involves, from fertilization to the delicate moment of childbirth. In the same revolutionary line, the black paintings of Óscar Astromujoff, illustrated by the mad and masterful poetry of Leopoldo María Panero, represent a hallucinatory vision of life. The result is the painting of a language or painted calligraphy. The drugged lucidity and expressive violence break with the usual and reclusive panorama of art that destroys halls and cultural centers as if it were a churros factory. Revolutionary, therefore, because it is intense, innovative and uncomfortable. Gabriela Esperanza's book relies on the inexhaustible power of art to make visible the invisibility of two issues that threaten humanity in the 21st century: environmental disaster and immersion in an increasingly digital world. Where is the revolution of this apparent obviousness that we all know? Well, very simple: through the fragmentary readings of groundbreaking novelists such as Karl Ove Knausgard, or the arachnocosmic concerts of Tomás Saraceno, or the telephotography of Trevor Paglen, the author draws intelligent conclusions and makes a forceful critique of the great capacity of art to recalibrate our place on the planet, to break the web that binds us and to learn to look beyond the opacity that tries to blind us. Finally, the certainties of Óscar Tusquets are concretized in one: he seeks emotion and here (in the world) he only finds a lack of transcendence. According to Tusquets, in the book illustrated with photographs by Eva Blanch, abstract art – a misnomer – does not find any kind of universal theme (friendship, love, passage of time, humor, memories, death). The revolutionary concept of the Tusquets tour is the fierce defense of figuration, an apology that contrasts with the huge dose of abstraction that fills our art galleries. Because figurative art is useful. They are revolutionary texts to the extent that they mix writings from thirty years ago and the ideas have not aged at all with reflections written today that awaken the reader and leave him no rest.

As Richard Wagner already pointed out in 1849 in his essay The work of art of the future , it will not arise from the dirty foundations of our current culture, nor from the disgusting foundations of our education, nor from the conditions that give in our modern civilization the only conceivable basis for it to exist. All this is only the artifice of an unnatural culture. The conceptual revolution configures systemic transformations of perception, interpretation, beliefs, relationships that oblige both human subjectivity and intersubjectivity to reorganize a whole and the parts attributed to it as a true transformation of knowledge and subject links - object

In these four reviewed books that we fervently recommend, both Astromujoff, Speranza, Tusquets, and Pompeia follow the wake of the artistic revolution, understanding it – separately but at the same time connected by a conceptual wormhole – as a new way to look at reality and, above all, to know how to convey it to neophytes who still go through life separating or labeling reality because we don't know how to read it.