Opinion

Now it's there, now it's not

In January 2006, the news broke: "The Queen Sofia Museum loses a 38-ton sculpture by Richard Serra." It seemed like a joke in bad taste, a completely implausible story, a wild story written by someone allergic to minimalist art. The headline was disconcerting and had elements of suspense that raised a series of questions: how was it possible that Queen Sofia had lost a work of such magnitude? Who had taken it? How had it been loaded? Where could they have hidden 38 tons in the form of four massive blocks of large steel? Had it been melted down for scrap? And the million-dollar question: who benefited from this mysterious loss?

In 1986, the American artist created the sculptural ensemble Equal-Parallel/Guernica-Bengasi specifically for the Madrid museum as part of the inaugural exhibition of the Reina Sofia References Art Center. An artistic encounter in time . Once the exhibition was finished, the museum kept it in its warehouse and in 1990, due to lack of space, it contacted a company specialized in the storage and transfer of works of art, which placed it outside from one of its ships, in Arganda del Rey. So far, all in order. In 2015, however, when the museum wanted to recover the work, it was discovered that the company that kept it had gone bankrupt and that the piece had disappeared, as if in a game of conjuring: now it's there, now it's not it is there

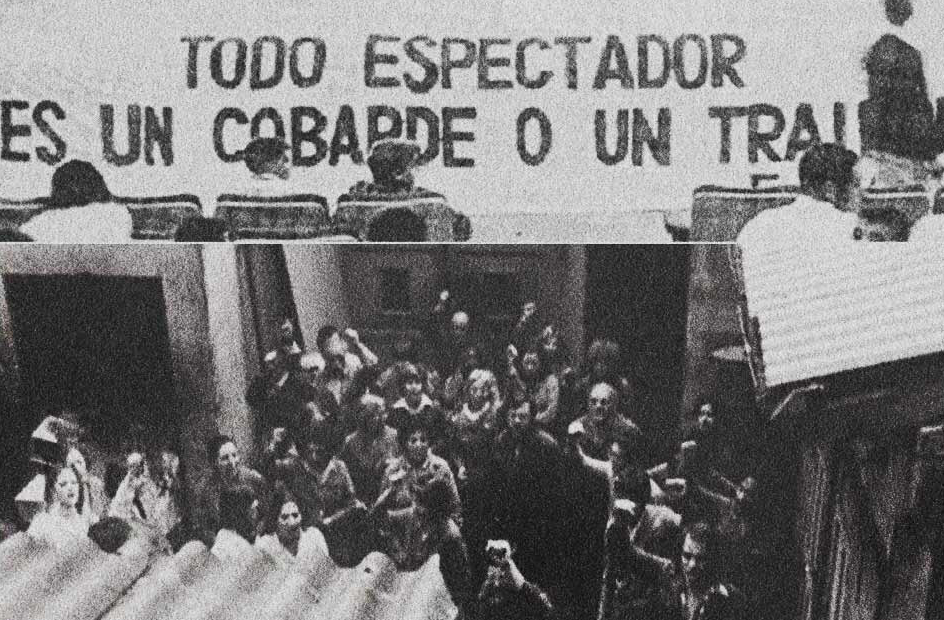

The case has never been resolved but, faced with the international scandal, the artist, accustomed to destroying many of his pieces after being exhibited, agreed to produce them again. Sixteen years after this vaudeville, the writer Juan Tallón publishes Obra maestra (Anagrama), a non-fiction novel or novelized chronicle about the events, in which about sixty witnesses follow each other between journalists, artists , judges, guards, engineers, gallerists, ironmongers, exhibition installers and also Serra himself. A choral story that travels over half a century where the author links the creative path of the sculptor, the police investigations, as well as various reflections on collecting and the laziness of the public administration that favored the passing of a something like that In this narrative, as in the case of the lost work, nothing ends up being what it seems at first glance: the doses of fiction that make up the text are like pills of reality and the historical facts, brushstrokes of a comedy of messes. Finally, a double question mark hovers over the book: is it possible that one day the first Equal-Parallel/Guernica-Bengazi will appear? And if they find it, what will the museum do with two identical sculptures?