reports

Fifty-nine Venice Biennales

The Venice Biennale has been the most important international contemporary art exhibition since its founding in 1895 - the first of its kind - and until the fall of the Berlin Wall. With the multiplication of biennials around the world - today, more than a hundred - the biennial has lost its referentiality, but not its ability to receive and stimulate the production of first-rate artistic proposals in the historic pavilions of the participating countries. In any case, in the course of its centenary history, the biennial has been a privileged portico of the arts (an Atrium Portos ) that over the decades has been able to host some of the most representative aesthetic debates of the artistic avant-garde: futurism , surrealism, informalism, pop art, conceptual art, land art , kitsch … An artistic and, at the same time, extra-artistic platform: a story full of political juggling, also of greedy commercial ploys, and where from modernism to today's art - Catalan creators have played a key role in their artistic, and often extra-artistic, proposals.

From the Anglada Camarasa scandal to Commissioner Eugeni d'Ors

Exhibiting at the Venice Biennale in 1905 meant for Anglada Camarasa to establish herself internationally, especially for the commotion caused by her early decadent works: with the shadows and miseries of the Parisian night - drugs, entertainment , prostitution - which shocked visitors to that fifth biennial. In contrast, the main plain of modernist painters - Casas, Canals - took the opportunity to present their most commercial production at the event, focusing on flamenco dancers and gypsies who caused a furor among the first tourists of the Serenissima .

The Noucentista generation, on the other hand, had to suffer the legitimation of the arts in the hands of the nascent fascisms during the interwar period. Beyond the works of Clarà or Casanovas in the shop windows of the Mussolini biennials, the most shocking case of this period is the one starring the figure of Eugeni d'Ors. After the Pantarca was attached to the Spanish phalanx during his "exile" in Madrid, he became acting commissioner of the Francoist pavilion at the 1938 biennial, defending with slang reactionary artists of the regime such as Pérez Comendador or a "convert" and unrecognizable Pere Pruna.

Jordi Colomer, Únete! Join us!. Pavelló Espanyol a la Biennal de Venècia 2017

Jordi Colomer, Únete! Join us!. Pavelló Espanyol a la Biennal de Venècia 2017

1954: Dalí vs Miró

Salvador Dalí wanted to enter the Sicilian biennial at the 1954 biennial. He had just sworn allegiance to the Franco regime and had come from the Vatican to visit Pope Pius XII, whom he demanded - without success - to grant him the nihil obstat - the papal approval - of La Madonna de Portlligat , a work in which Gala was represented as the Virgin. But Dalí, in Venice, did not arouse the desired attraction, particularly among the Italian political sector, immersed in the republican transformation of the country. The figure of Joan Miró, on the other hand, aroused much more admiration, and this is probably why in 1954 he was awarded the Grand Prize for Engraving. An award, however, that Miró started as a defeat, given that the first painting prize was awarded to his generation mate and rival Max Ernst, who had just published an essay against painting! In any case, Miró considered the event an "international showcase of barracks", and designated it as the "stinky salad of Venice".

Tàpies: reserved matter

It is well known that the post-war Catalan generation, without exception, used the Francoist platform in Venice to consolidate itself internationally. The most memorable case is that of Antoni Tàpies, who during the fifties and sixties participated up to four times in the Spanish pavilion curated by González Robles, until the award in 1958, of UNESCO and the foundation David Bright, who catapulted him internationally. That same year, as the artist embarrassedly admitted, he decided not to participate in the pavilion again after discovering that his works had arrived in Venice in boxes with the stamp "propaganda material" ... He returned to Venice in 1993 with Rinzen, and was awarded the Golden Lion.

Antoni Abad, BlindWiki. Pavelló Català a la Biennal de Venècia 2017

Antoni Abad, BlindWiki. Pavelló Català a la Biennal de Venècia 2017

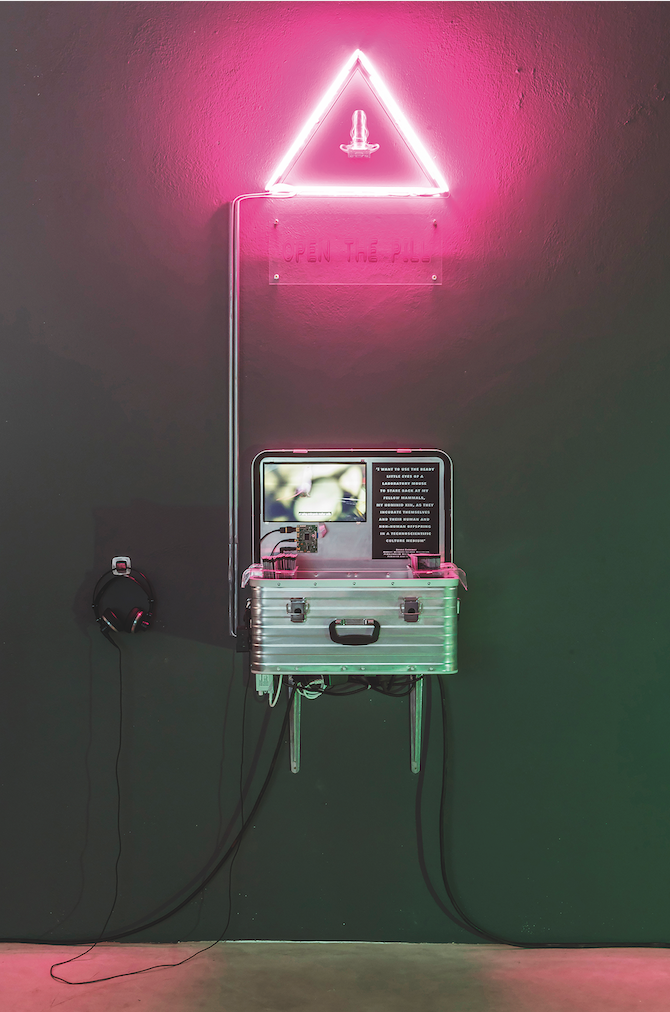

Miralda, Arranz-Bravo, Muntadas, Colomer

The best artists in the country have participated at one time or another in Venice, and almost always with exhibitions of great importance in the rooms of the Spanish pavilion of the biennial. It is only necessary to remember the commotion caused by Miralda's exhibition in her project Honey Moon (1987), a large production in which a marriage was staged on an elephantistic scale, with all its peculiarities and traditions; or the great montage by Arranz-Bravo and Bartolozzi, who in the exhibition Universal Sizes of 1981 painted one hundred and twenty-six canvases that they made to paint all possible sizes of the pictorial frame. We must also remember the latest speech by Antoni Muntadas, who transformed the pavilion into a waiting room from which to propose a critical analysis of the 110-year history of the Venice Biennale. We also think of Martí Manen's Dalí review in Los Sujetos (with Francesc Ruiz, among others); as well as the project –topist, activist and performer– Join Us , by Jordi Colomer. All this in a dynamic that in the last decade has advanced in parallel with the exhibitions of the Catalan pavilion (curated by Valentín Roma, Frederic Montornés, Jordi Balló, Pedro Azara, Chus Martínez or Mery Cuesta) in the old salt warehouses of the eternal and immutable Isola nobile .

In the image Ignaci Aballí, Correction, Spanish Pavilion at the Venice Biennale 2022.